I’m not the only one wrong here on certain points, either. What makes me certain about some items is that I have read them over and over again. One thing I have discovered is that many of my sources are just parroting each other. When I actually go to take a look for my own self I often discover that someone somewhere up the old food chain was dead wrong. The other thing I’ve discovered is that there are only two types of old booksellers: people who sell books like pots-- wherein the only thing they know is jargon on condition-- and certifiable book GEEKs, who frankly know everything. It is thanks to the confluence of Geek data that I am now able to accurately construct a picture of the Private Lending Library Industry of the 1930s.

“Yea me,” I am sure you are thinking. It has sex! Lots of sex! Does that help?

(Pictured is Marie Prevost, who was the subject of an unfortunate joke after having been found dead, face down in her apartment, her body nipped at by her pet dog. In the play Legends, Carol Channings’s character warns Mary Matlin that it wouldn’t be safe for her to die with the dog on the premises, unless it had been trained to operate a can opener.)

Previously I had been led to believe that the Private Lending Library industry was something of a dustbin affair, generally relegated to a side business run out of taverns, tobacco shops, and pool halls. And it was. That’s part of it. But that’s not all or even most of it. And I can thank book dealers holding actual books from some of these libraries for setting me straight.

The term Private Lending Library is not any more descriptive than Public Lending Library. Both would indicate a place where books are stored and then lent out. That isn’t at all what a Private Lending Library is, which is why I have chosen to substitute the term Commuter Library. Unlike a real library, the Commuter Library is a for profit business which rents books. The rental is charged up front, usually at three cents a day. They appeared out of nowhere in the 1920s, bloomed to 40,000 locations during the Depression and then completely vanished by the early 1960s. Or so the story goes.

The actual story is a little bit more complicated. During their heyday, which is the Depression exclusively, Commuter Libraries were a recognized market segment. Several publishers, most with ties to the pulps, plied this sector. (I started my research into it because my subject Alex Hillman worked for one of these publishers.) When the market has been handled at all, it has been as an adjunct to either the history of pulp magazines or detective fiction. Such treatments have failed to capture the market’s scope or even to define what it really was.

The term Private Lending Library comes to us from England, where this sort of set up existed since the days of Charles Dickens--and most likely a lot earlier. (Perhaps just half past Shakespeare.) In England these institutions were known alternatively as Private Lending Libraries, for small ones, or Public Lending Libraries, for larger ones. There is a very frequent assumption that the mechanism was simply imported into the United States. That they didn’t exist as a recognized distribution method in the United States prior to the 1930s is telling. Publishers in the United States referred to the market as the ‘Bookstall Rental Market’ or the ‘Private Circulating Library Market.’

Again, the word ‘library’ is problematic. The Commuter Library was no more a library than a bowling alley is a shoe store. Just as a bowling alley may rent shoes, their relationship to the shoe business is incidental to an entirely different trade. The same was true of Commuter Libraries during most of their existence, sans their actual heyday.

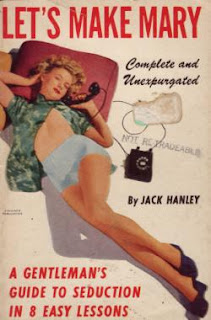

I had best get on with the sex. Commuter Libraries owe their existence to sex. Providing sexually oriented reading material to the public was their original reason for being. To say that this was most of what they offered is to play up an oft repeated and I think false perception. In fact, during the Depression the vast majority of their offerings were not of this nature.

The Commuter Library was a vestige of the first paperback boom and a literary fad called Flapper Fiction. (Covered in The Laughing Wallflower on Hil-Gle.com.) Flapper Fiction started in the pulps near the end of the 1910s. It spawned an absolute craze in the pulp world, launching dozens of titles and drawing female readers to the pulp racks for the first time. Its two distinguishing traits are: (1) that it is extremely graphic and unsentimental about its subject and (2) that its only subject is sex. As intended, it was erotic fiction written by women for women.

Flapper Fiction is itself a backlash against the previous generation’s Suffragette school of female writers. The Suffragettes were very influential, having won for women the right to vote, largely created the 40 hour work week and brought an end to child labor. Their last true act as a political force was the enactment of Prohibition—something for which the Flappers were not overly grateful. Theirs would have been heady footsteps to follow in, if the Flappers were even remotely interested in doing so. And they weren’t.

Flapper Fiction was pure backlash, analogous to Punk Rock. Flappers named the music of their generation Jazz or Rhythm & Blues, both code words for sex. They wore galoshes on their feet (no shoes, just rubber rain boots which they kept open at the flaps). What the galoshes were meant to signify is open to speculation. (It it did have the desired effect of causing one’s mother to want to tear her hair out.) They took being un-corseted to another level. Thanks to Freud, they felt perfectly empowered in reducing everything ridiculously to sex. Their entire literary focus was a meticulous exploration of the ins and outs of ‘it’.

It had its moments. You will note our flapper here is in a football stance. Football was the new man’s game at the time. Just as Flapper Fiction was replacing the Suffragette in literature, football was replacing baseball as a national pastime. Weirdly, the same thing happened to both Flapper Fiction and football. Once it was demonstrated that there was money to be made at either, the armatures lost control of the racket.

To cut the Flapper Fiction writers some credit, the majority of them were already pros. Flapper Fiction proved to be just a little too hot for the pulps. The sleaze dropped from X to R fairly quickly. Even then, it was getting the pulps in trouble. The U.S. Post Office and the government of Canada cracked down on the magazines. Soon Flapper Fiction in its least distilled form found its way to the paperback market.

Paperbacks had been around since the 1840s, but this was their initial real boom in popularity. At first, Flapper Fiction was all that appeared in paperback. By the time Flapper Fiction arrived in paperback form, the fad had been renamed as the ‘Sex Novel’ genre. But it was not to last.

The paperback format, that is. The Sex Novel soon became a staple genre amongst the lowest hanging fruit of the publishing industry—a product that sold consistently, although somewhat clandestinely. It became essentially the women’s section of the Under The Counter Market. (Covered in Hil-Gle.com.)

It was the paperbacks themselves that did not catch on. As a format, the paperback’s only real advantage at the time was in being cheap to ship. It was not all that much cheaper than a real book to produce. In many cases, it was more expensive than a magazine. It could, however, be mailed in little brown envelopes without much fear. Or dead shipped in mass to barber shops, pool halls, taverns and other Under The Counter markets. The boom in sex novels caused a temporary spur in demand for

paperback offerings of all kinds. Besides smut, many mail order houses were printing up the classics. Condensed books of various facts, dictionaries, encyclopedias and atlases were soon also finding their ways beside the girls smut. All of this was well and good, except for the product.

Paperbacks of the time were destructo books. Few survived their first reading. They had the shelf life of fruit. Once ordered, they were seldom reordered. What their brief appearance did demonstrate was that there was a demand for this type of material. The condensed cyclopedias and girls smut stayed on—it just became hard bound. That is the true origination of the Commuter Library.

The Commuter Libraries went from the Pool Halls to the drug stores in a blink. It was in drug stores that they would hold on longest, the last publisher leaving the market in 1962. It was a good side business for these stores. Invariably the girls smut would be parked on a shelf in the aisle with feminine hygiene products.

It was actually a variable set up, fully customized to the venue. There were local agents who would move the books around to keep the assortment from getting stale. To the retailer, the margin wasn’t in the up front rentals, but rather in the occasional inadvertent act of shrinkage. (Our customer claims she ‘lost’ the book. Please find a way to add $1.50 to her bill without mentioning Sultry Wanton Youth Lost in any way, shape or form.) As time went on, the erotica gave way to other genre offerings. But a stiff dose of sex was always there, even when it was dressed as other offerings.

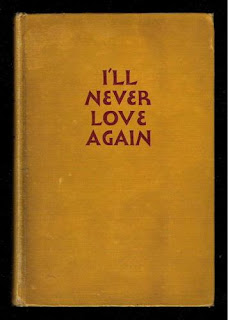

As opposed to being flimsy, most Commuter Library books were industrial, nearly text book like. Many of the printers were in the text book trade. These books had to survive transit and the wear of multiple hands. A product standard specific to this market was set fairly quickly. Only the thickest cover stock was suitable. The books needed to have their titles embossed on them, preferably in recessed black letters. And the physical covers had to be bright colors. All of this was in preparation for the eventuality of the dust cover being destroyed. Even without a dust jacket, the book still had to draw the eye. Dust jackets were also the heaviest grade available.* Retail prices were capped at $2.00, which was average for the day. Wholesale prices depended on the book’s level of circulation (whether it was new or had been moved in from another bookstall.) The three cents a day went to the vendor, but all other fines went to the store. The books were 60 thousand words, roughly 289 to 300 pages. Any book that was consistently being rented would not be moved to another store.

As opposed to being flimsy, most Commuter Library books were industrial, nearly text book like. Many of the printers were in the text book trade. These books had to survive transit and the wear of multiple hands. A product standard specific to this market was set fairly quickly. Only the thickest cover stock was suitable. The books needed to have their titles embossed on them, preferably in recessed black letters. And the physical covers had to be bright colors. All of this was in preparation for the eventuality of the dust cover being destroyed. Even without a dust jacket, the book still had to draw the eye. Dust jackets were also the heaviest grade available.* Retail prices were capped at $2.00, which was average for the day. Wholesale prices depended on the book’s level of circulation (whether it was new or had been moved in from another bookstall.) The three cents a day went to the vendor, but all other fines went to the store. The books were 60 thousand words, roughly 289 to 300 pages. Any book that was consistently being rented would not be moved to another store.

Taverns, pool halls, tobacco stores and barber shops had an arrangement similar to those of the drug stores, but were heavier on the fact manuals. The trade didn’t explode, but rather gradually evolved as more genres were introduced. Barber shops and drug stores were good for westerns. The manuals started becoming self help building project guides and moved into hardware stores. Self help expanded to business guides. Occasional inflammatory manifestos and exposes started to appear. (Did I mention sex manuals? Dozens.) It was all about where the stall was and what you thought you could sell there.

Concurrent with this was a second distribution network built out from the railroad lines. This helped spread the product to rural areas. Commuter Libraries were set up in train depots, in hotels and in general stores. Often a very large display would appear in general stores, since these were likely to be in places where no other library was present.

Concurrent with this was a second distribution network built out from the railroad lines. This helped spread the product to rural areas. Commuter Libraries were set up in train depots, in hotels and in general stores. Often a very large display would appear in general stores, since these were likely to be in places where no other library was present.

It was off the rail lines that most of the growth in this business had taken place. By the 1930s there was a specific emphasis on capturing the commuter rail market. Several publishers had established systems wherein it was possible to rent a book in Boston and then return it in Los Angeles. Again, here the margin was actually in getting the customer to buy the book. That the books were generally salacious in nature and not commonly available anywhere else eased the sale process. In any case, if you didn’t finish the book on the train, you needed to buy it because you couldn’t take it to the hotel with you on a rental. It was a bit of a scam. The publishers were focused on it because it worked so well.

(It was featured in several movies and radio shows of the time.)

This is fairly much how the business functioned right up until the Depression set in.

Print runs seldom exceeded 12,000 copies. At most there were a dozen publishers, each introducing a few titles per month into the market. Translations, imports and the occasional reprint (Bulldog Drummond) did surface here on occasion, but the majority of the novels were appearing in book form for the first time. Many of the novels were expansions of 40,000 word stories previously published in pulp magazines. Some of the novels were constructed out of two or more works which were cobbled together into a whole. This was a No Royalty market, paying 1/4th cent a word—half the standard pulp rate—and the finished product often reflected this. Unlike the meticulously edited pulp magazines, books in this market were rife with typos and other incongruities. It was the lowest paying professional fiction market of its time.

Print runs seldom exceeded 12,000 copies. At most there were a dozen publishers, each introducing a few titles per month into the market. Translations, imports and the occasional reprint (Bulldog Drummond) did surface here on occasion, but the majority of the novels were appearing in book form for the first time. Many of the novels were expansions of 40,000 word stories previously published in pulp magazines. Some of the novels were constructed out of two or more works which were cobbled together into a whole. This was a No Royalty market, paying 1/4th cent a word—half the standard pulp rate—and the finished product often reflected this. Unlike the meticulously edited pulp magazines, books in this market were rife with typos and other incongruities. It was the lowest paying professional fiction market of its time.

That said, there were some authors who worked exclusively in this field, most of them in romance or erotica.

It was never a particularly large market. For all of the publishers involved save one, Phoenix Press, it was a sideline. There were no real best sellers here, although several books did have multiple printings. Over the years the market built up a considerable inventory. So much so that there is no shortage of former Commuter Library novels in the antiquarian book markets. Even after the number of outlets in the market exploded during the Depression, the output of the publishers did not.

Once the Depression hit (1929), three cents a day rental didn’t look so bad. Book retailers were particularly hit hard. Remaindered inventories of foreclosed book stores flooded the Commuter Library market. Larger Commuter Libraries began sprouting up in cities. It seems that many businesses that had been operating Commuter Libraries as a side business decided to expand. All of these factors contributed to the jump in outlets.

(At 40,000 outlets the Commuter Library market was one tenth the size of the pulp magazine distribution system. There probably was quite a bit of overlap. Just as today wherein most game stores handle comic books, but few comic book stores handle games, all Commuter Libraries probably handled pulps but few newsstands operated a Commuter Library.)

The Depression did not help the Commuter Library publishers, either. Firms steadily dropped out of the market, with the number two publisher William Godwin (under the leadership of Alex Hillman) leaving in 1940. Eventually the market became indistinguishable from the overall used book market: the Commuter Library mechanism itself was a method of producing income from slow moving inventory. By the end of the war, there were only two publishers still actively servicing the trade—both of whom had no other lines of business.

In 1948 the final two publishers, Phoenix Press and Arcadia House, merged. The industry became a one firm business. Arcadia House was eventually absorbed into a paperback imprint and continues in renamed form to this day. By the time the last drugstore rental bookstall closed in the 1960s, the erotica this industry had once exclusively peddled had become a staple of the paperback market.

The industry produced no memorable works. During its heyday reviewers boycotted covering its offerings. Some of the more proven titles migrated to paperback and a few are still in print today.

The only successful publisher to have emerged out of this industry was Alex Hillman, who will be the subject of Hil-Gle.com’s next update.

No comments:

Post a Comment