Just as the Beatles didn’t invent rock and roll, Disney hardly created the concept of exploiting the names and images of fictional personas. By the time Disney showed up, the various steps of the process had already been traced out. Disney’s first employer, Walter Lantz, had a full-fledged licensing department, as did all of the early animators. Exactly how much income the animators made off of anything other than ticket sales is unknown. What we do know is that such firms considered income from merchandise and licensing actively worth pursuing.

Many companies list their trademark as an asset. Trademarks, service marks, slogans, jingles and mascots are all usually valued under the broad heading of “Good Will.” In most cases, these Good Will items are subservient to the company’s identity or products. Taurus is the name of a car Ford makes. It is not an independent entity nor a character of any depth. Unless you are a real Ford nut, chances are you aren’t going to be compelled to buy a purse with the Taurus logo on it—and no one will feel the need to make one. With the exceptions of Coca-Cola and Harley Davidson, few companies make money off their trademarks alone. (Sports teams are entirely a different business with a history which I have excluded.) Firms in the Character Management business, by contrast, do nothing but make money off of trademarks—specifically fictional characters, In most cases the firm does not own the characters, but simply acts as a pimp for the owners. It’s a strange business with a very unusual history.

It’s also an ancient business, with roots that you can trace back nearly as far as popular fiction itself. The reading of fiction has been a pastime since the start of moveable type. Despite the popularity of the performed play as a medium during Shakespeare’s time and before, none of them featured continuing characters. Serialization—reusing a character or group of characters—in several stories, or in a progression of stories, does not make a showing until late in the Enlightenment. By the time the Romantic period started rolling clapboard, novels featuring the same characters over and over had become something of a staple. Much of this was juvenile, similar to children’s books today and quite a bit of it was pornographic. (1)

(1) Smut may actually date back to the Renaissance. Calendars featuring decapitation and torture—produced for the amusement of the masses—certainly do. We have only second hand references to smut materials, novels about rapists and other actors of mayhem, but no existing examples of such.

Popular Fiction, as opposed to Literary Fiction, came into its own during the Romantic period. Popular fiction was much more about turning a profit on mass appeal than the hard bound form. Our protagonist of the clapboard novel is far more likely to be an escapist vehicle than the embodiment of a theme or metaphysical point. It’s someone you like. It’s someone you cheer for. It’s someone you feel through. (2)

(2) Literary Fiction also came into its own during the Romantic Period. And it’s just as commercial, although the audience is never broad. The intention in Literary Fiction is to immerse the reader in detail, to make them seem part of a new world not of their own making. Popular fiction more or less assumes the character and world, rather than defines it. There’s a lot of Grand Theft going on in both forms, but the Popular kind is much more brazen about it.

Coming up with a likeable character was the aim of most early Popular Fiction. If the author chanced on a character that worked, there was no reason not to do it to death.

There are actually three different types of Character Management, with three distinct histories, which we will be dealing with here. Our focus will also be beyond the printed word. An author using the same character in several books or works of short fiction is a form of Character Management, but it is the most basic form. The big money is not now --nor has it ever really been-- in literature, but rather in using the character in a medium other than literature or as a product spokesman. That history is a much less ancient and is quite complex.

Given that characters make such good trademarks and pitchmen, it is a wonder that characters contrived and owned by corporations have such a comparatively short history. That is the second type of Character Managements. The third type of Character Management takes place when a character in the public domain is turned to private use. There is also a variant of this third type of character management, wherein a previously author-owned or corporate-owned character reverts to the public domain. Oddly, both variants of this final type of Character Management involve Christmas. And Paul Bunyan.

We will start with the third type of Character Management first, since it is illustrative of all the varieties. For the third form, the only two characters who are top of mind examples are Santa Claus and Paul Bunyan. (3) Weirdly, both were real people at one time, as was the other well known example, Uncle Sam. .

(3) You might also include Pecos Bill and Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer, but neither really qualifies. Pecos Bill comes out of the Tall Tales literary tradition and seems to be a one writer creation. Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer, though long-lived, is a proprietary character, an example of the second type of Character Management. It is actually the last performing asset of the Montgomery Wards Company. (Today a Character Management firm called Character Arts, LLC manages Rudolph’s licensing for a holding company called Rudolph Company, L.P)

Santa Claus came late to even literary fame. You will note that Jolly Old Saint Nick is not mentioned in the Dickens’ story A Christmas Carol. This is because the tradition of Father Christmas giving toys to children is not an English one. In fact, Christmas itself wasn’t that big of a deal at the time the story was written. (4)

(4) Christmas became popular partially as a result of the story’s popularity. Again, character management history has a hand here. Although A Christmas Carol was certainly a well read story, it owes quite a bit of its popularity to the many stage adaptations of the tale—and later movies—which have been made.

Saint Nick wasn’t originally even associated with Christmas, but rather a pagan celebration taking place on December 25th. The actual Saint Nick himself is said to have attended the First Council of Nicaea, where it is believed that he may have added some specifically Jew-bashing language to the New Testament. (5)

(5) This is what is believed about the saint. What his involvement, if any, was at the Council of Nicaea, is not known. It’s doubtful that any final text for the New Testament was set forth there. Early on, the Christmas celebration had a very anti-Semitic character to it.

At some point the Saint’s bones were stolen and brought to Bari, Italy for use in displacing a pagan deity known as the Grandmother. Previously it was she who brought children gifts on December 25th. Then there was a period of pagan and Christian acceptance of Santa Claus. Flash forward and the tradition was brought to the new world where first a story and then a poem were written about the saint. Then Coca-Cola made him fat and started using him to pitch sugar water.

Given his longevity, Santa Claus is something of an open trademark, a true public domain superhero. No royalty need be paid anyone for using his image or name. Similar, but not quite as ancient is the character of Paul Bunyan. Like Saint Nick, Paul was a real person, although he wasn’t known by that name. He was a very large, drunken French Canadian whose exploits became the stuff of camp legends.

Eventually these camp stories dovetailed with an 1840s literary movement somewhat similar to today’s Magic Realism. The premise of this literary genre was to create origin stories defining aspects of the new world, as told as if they had originated in Greek Myth or the Bible. The legends of the drunken giant French logger somehow also became grafted to the Tall Tales oral tradition as well as the North American Myth literary genre. (The Tall Tales movement came after the North American Myth genre. Tall Tales grew out of a fad of telling very inventive obvious lies as after dinner entertainment.) By the time Paul Bunyan appeared in a 1906 wire service fiction piece, the two trends had weirdly combined. (6)

(6) Newspapers of the time often ran short pieces of fiction. They were used as filler copy in eastern papers with evening editions. The wire services made them available to all subscribing newspapers. In the case of the Paul Bunyan tale, it originated with a western newspaper which then offered it for syndication. It was, however, a single story and not part of a series or serial.

But we are not through combining artistic trends yet. Much of American sign advertising of the time was drawing on the Craft’s movement. The Crafts movement was a reaction against mass production—or against mass mass production—and towards preference for objects which at least looked handcrafted. At first borrowing from this trend manifested in advertising with hand lettered signs, but then it became oversized ‘crafty’ examples of whatever the establishment sold being used as a sign. You see a lot of giant saddles, cups and eyeglass frames. Add Paul Bunyan and you have a theme.

That’s pretty much what happened. Paul Bunyan became America’s first original public domain fictional advertising spokesman. He lends a reason for all of this oversized stuff, a ready-made trademark. The next thing you know there are all sorts of Paul Bunyan-themed establishments popping up.

In 1914 the Red River Lumber Company began using Bunyan as a spokesman and issued a series of chap books and pamphlets featuring him. Most of the Paul Bunyan stories we have today came directly from this material and little of it is related to the original oral stories. (7)

(7) Red River’s copy writer William Laughead added Babe the Blue Ox and slanted the character firmly into the North American Myth genre.

That said, Red River made few attempts to enforce any exclusivity to the character. They were more or less like every other establishment that glommed onto Paul Bunyan. In a way, Paul Bunyan constituted something of a discovery, a first in the world of marketing.

By sticking Paul Bunyan’s name or image (or big fake boot) on an otherwise anonymous institution (like a lumber company or six table greasy spoon), the business gains instant identification, instant recognition and an instant transfer of good will from the fictional character to the business. Why anyone would trust the implied endorsement of a fictional giant Frenchman is beyond me, but they did. And they do. Long before celebrities got into the endorsement routine, fictional characters had been plying the trade for decades. Paul Bunyan was amongst the first, if not the first. (8)

(8) It’s a possible tie with Santa Claus and perhaps Uncle Sam. All three started cropping up in advertising at about the same time. We should also mention various Presidents (Abe Lincoln and all of the founding fathers) who have also served in the same function, having their public domain names and likenesses slathered over insurance companies, banks and department stores. All of this is a turn of the 19th century advent.

People wanting a mug or a clock or a hat with their favorite character’s image on it is actually the lagging portion of the business. Whereas Paul Bunyan made the leap from public domain fake historic figure to the spokesmodel for campsites and low rent amusement parks, the traditional route is for the character to hop from one medium, the printed word, to some other medium. Which would require the existence of other mediums. So this is where I fast forward.

Not quite.

There are plays and comic strips to consider first.

Adapting novels for the stage is old hat, one would think. This is not really the case—and not at all the case at the time. The legitimate theater is its own genre, has its own culture. Play writers are not novelists, in general, and did not borrow from novelists, in general. A novelist or short story writer might be an aspiring playwright, but the guy who writes for the legitimate stage is really the top of the food chain. No matter how well a novel might have done, it was seldom if ever adapted for the stage. This makes little sense from a modern perspective, but it was true of the snobbery enclosed theater culture of the time. This was not the case with Opera or its evil spawn, musical theater or its sad relation, the popular theater. Those forms were (and are) kleptomaniacs. (9)

(9) The Musical, a show with plot and musical numbers interwoven, did not exist early on in the era. The start of Character Management coincides with the origins of the Musical form.

Buffalo Bill Cody owes his fame and once considerable fortune to both Dime Novels and the popular theater. Cody was ‘discovered’ by aspiring Dime Novelist Ned Buntline, who was actually out to write some adventures about Wild Bill Hickok. While being approached about the Dime Novel project, Hickok pulled a gun on Buntline and told him to get out of town. Buntline met Cody on the way out of town and decided to do novels about him instead. Buntline’s novels proved so popular that Cody began appearing as himself in plays based on the magazine stories. It was this positive experience on stage that inspired Cody to start his wild west show.

Enter Sherlock Holmes. Holmes is the first sensation of the magazine fiction era. His serialized adventures kept readers coming back to the stands to pick up issue after issue of The Strand magazine.

It’s the right thing at the right time. In the previous era, magazines didn’t have the reach and there was no critical mass of literate people to reach. With the stage having been set by the steam fed press and advances in education (and medicine) a nationwide star was sure to show. Holmes was the first.

There was only so much Sherlock to go around. The popularity of the character led to increased demand for additional stories. Or knock offs. Holmes will figure twice in the history of character management, but his first impact was in the popular theater. Within a year of the character’s appearance, his various exploits were being adapted for the popular stage. Since it was a serial character, there was a steady stream of new material to adapt,

Silent films would follow shortly, but in the mean time Sherlock Holmes was spearheading a revival in regional touring theaters. This trend jumped the pond and soon popular fiction of all kinds became fodder for the touring troupe. The writer of the Wizard of Oz made more money off the stage adaptations of his work than he did off the book itself. And that’s before the movie. Two different musicals about the Wizard of Oz toured Broadway before the first film was made. The film we are all familiar with is actually the second movie adaptation and does not borrow from either of the previous musicals.

Concurrent with Sherlock’s popularity on stage in America was his impact on reviving the Dime Novel trade. Holmes came to American shores primarily in book form, but his impact on story papers in England inspired many an American Dime Novel house to try something similar. The firm which really originated the field of Character Management started out doing just this. But it was sort of an afterthought.

Originally the firm had taken the novel tact of licensing the name and image of an actual living person to sell their Dime Novels. The firm was called Street & Smith and their flagship Dime Novel spokesman was none other than Buffalo Bill Cody. There were other firms in the Dime Novel business either licensing or just using the names of actual out west personalities of renown. Both Jesse James and Billy the Kid had their own Dime Novels.

Using real people does have its risks. The Dime Novels got away with fiction in the name of Jesse James, but Billy the Kid’s family sued. Even when you had permission to write fiction about a person, as Street & Smith did with Buffalo Bill Cody, you did take a chance that your real life cowboy might meet an untimely end in real life, as that other famously officially licensed cowboy Wild Bill Hickok did.

When it came to doing a Sherlock Holmes knock off—and all of the Dime Novel houses felt compelled to do one—there was no real person to model off of. And you couldn’t knock Sherlock Holmes off too closely, because the author and his agents would sue. Of course, as with The Strand, the folks at Street & Smith could have waited for a writer to present them with a compelling character which they then could hope to exploit.

Street & Smith wasn’t going to wait for anything, Detectives are hot. They want a detective, just like Sherlock Holmes, but with even more of a master of disguise bent. It was the business end of Street & Smith, not a writer, which crafted the character. Unlike The Strand or any other fiction publisher of the time, Street & Smith wasn’t going to sit back and wait for inspiration to strike one writer or to be bound by the output of a single hack. They came up with the name, the character details, the general plot formula—and then they assigned it out to writers. This puppy was going to roll.

Although this seems like something of an obvious idea, Street & Smith was the first to pull it off in fiction. Their character, Nick Carter Master Detective, was a big hit in Dime Novels and followed Sherlock Holmes into the land of film adaptation. Unlike Sherlock Holmes, which relied on the output of a single writer, there was as much Nick Carter out there as the public would buy. Nick was so popular that even his kids had their own magazines. Although never as popular as Sherlock Holmes, new Nick Carter novels were being produced as late as the 1980s. And Street & Smith didn’t have to split the take with any of the hacks it hired. (10)

(10) All of that said, most of the early run of Nick Carter was the work of a single author. Street & Smith came to excel at the business of finding hot hands to write for them. And they helped the writer out as much as they could. Beyond providing the character, Street & Smith editors frequently also mapped out the plots and handed out research details. This system became very well honed.

(If you want a glimpse into how the Street & Smith fiction factory worked, pick up a copy of the movie The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.)

Street & Smith had inherited a “one risk” form of writer payment, which was standard in the Dime Novel industry. As opposed to paying royalties, Street & Smith made a one time cash payment up-front. It was standard in the Dime Novel industry for the writer to give up all rights to his work. (This is one of the reasons fiction in Dime Novels was often not of the highest quality.) If anything, providing the author with a ready-made character was more of an enhancement to the ‘one risk’ system than any real effort at controlling profits from other mediums. They really weren’t thinking beyond Dime Novel dominance at the time.

The Teenaged Mutant Ninja Turtle effect, wherein a character sprouts up in one medium and then is suddenly everywhere, had yet to happen. But it was about to.

Dime Novels at this point were feeling some competitive heat from a different format of magazine called the Pulp. (11)

(11) Historians see more distinction between the Dime Novel and the Pulp than the publishers ever did. Dime Novels were always in flux as a format. They started as magazines similar in form to your average Old Farmer’s almanac. Shortly after the Civil War, they began splashing stencil color on their cardboard covers. After that, the cardboard covers were replaced by a new process that splashed finely separated color on newsprint. Once slick presses became more prominent, the four color splash on newsprint cover was replaced with a four color litho slick cover. At that point, around 1920, a Dime Novel is a Pulp. In its end state, the only real difference is that what we call Dime Novels are center stapled whereas Pulps were perfect bound. But it isn’t entirely that uniform. At no time did the publishers of Dime Novels or Pulps (or pulp digests, for that matter) think they were in different businesses. They were all in the same impulse buy fiction business. The formats were nothing more than printing mechanics. When a critical mass of Pulp magazine presses came on line, most of the existing Dime Novels, including Buffalo Bill, Nick Carter, Breezy Stories and Young’s Magazine, made the switch to pulp.

Pulps weren’t primarily aimed at the juvenile or what we today call the YA market. At least not to the extent that that the Dime Novels had become pegged as. As the pulp niches started to expand, they came to steal the older demographic section of the Dime Novel audience. Pulps experimented a lot, which was a draw to younger readers. Genres which had found only slight expression in hard bound or slick magazine form often became staples of the pulps. One of the early pulp hits was an American science fiction character called John Carter Warlord of Mars. (Currently the star of a new Disney movie.) Carter was such a big hit that it “inspired” not just other pulp stories, but entire magazines and a pair of comic strips. None of this “inspiration” found its way to money flowing back into the originator’s pocket.

(Rex here is something of an imitation of an imitation--and a later one, at that.)

Carter’s author, Edgar Rice Burroughs, was feeling anything but flattered by all of this imitation. When a second creation, Tarzan Lord of the Jungle, also caught on, Burroughs became committed to controlling all aspects of the character. If there was any exploiting or knocking off to be done, Burroughs decided that he would be the one doing it. It was he who guided the character into comic strip and movie form, going so far as to create a company just for this purpose. His are the footsteps all subsequent authors have followed, really the first Teenage Mutant Ninja Millionaire.

Or it could have been the Yellow Kid. The Yellow Kid was a comic strip character who appeared in several New York City newspapers. Largely forgotten today, the kid’s bald face and oversized shirt once appeared on everything from chewing gum to whiskey to billboard advertisements. (12) That the character was a major draw was without question, but there were problems involving its ownership. It was in the aftermath of the licensing morass the Yellow Kid created that newspaper syndicates began being more proprietary about their features.

(12) Despite the licensing issues, the Yellow Kid remains a property available for licensing. He was last seen in a packet of stickers dispensed by gumball machines in the 1970s.

The actual creation of licensing departments started with the newspaper syndicates. The film industry, that other peddler of cute anthropomorphic squiggly lines, took a little longer to get its act together. Case in point is the above clock, which has been in production since 1920. It started as either an imitation of Krazy Kat or Felix the Cat. (13) This would be the last unattributed knock off ever tolerated. Even start-ups like Disney lawyered up.

(13) Felix the Cat started out as an unattributed adaptation of Krazy Kat, just to muddle matters further. Eventually the animator defined the character away from its source of ‘inspiration’.

Despite the obvious money to be made at it, there still wasn’t a single business or even a lawyer specifically in the Character Management field as yet. But it had become an established business function and revenue stream. Sometimes licensing has been so successful that it constitutes the only exposure the character has to the public. Today Betty Boop and Felix the Cat appear only on licensed products. Buster Brown had a much longer career as the pitchman for a shoe store chain than he did as a comic strip character. The same could be said about Popeye and Kayo. If it wasn’t for a musical, Little Orphan Annie would have vanished from the funny pages long ago.

Not only do characters fade from their original mediums, mediums themselves also fade. While the comics syndicates and animators were blazing the trail to increasing the revenue streams of made up personas, Character Management originator Street & Smith was contending with another problem altogether. Dime Novels were dying.

Buffalo Bill didn’t have the pull he once did. Nick Carter was now way long in the tooth. They did try to keep the Dime Novel form current by creating a new type of character, the Joe College All-American in the form of Frank Merriwell. Merriwell had followed the same track as Nick Carter, having leapt from the dime novels, to the movies to the comics pages. And it was the product of considerable corporate guidance.

But by the mid 1930s the Dime Novels were dead. (14) And converting them into pulps had not helped. Neither Nick Carter, Buffalo Bill nor the new Frank Merriwell survived the transition from Dime Novel to Pulp for long. A new medium, radio, was killing all of the magazines and had hit the pulps particularly hard.

(14) They would have died sooner, but they were kept in print by two waves of nostalgia crazes: first for the Civil War and second for the Gay 90s. Street & Smith itself not only played both waves like a fiddle, but were buoyed by the introduction of Frank Merriwell, which remained popular in Dime Novels through the 1920s.

Despite the downturn in their core business, Street & Smith was able to hold on. First, they had diversified into other fields of publishing, notably in sports fandom. Second, they owned a part of the Yellow Kid. That they had licensing money coming in from a comic strip character (that they only sort of half owned )may have helped loose some of their entrepreneurial juices. Whereas most publishers viewed radio as one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse, Street & Smith offered its characters to the medium and actively fed it content.

And it wasn’t as if Street & Smith didn’t have something to offer. Buffalo Bill and Nick Carter were familiar to generations of potential listeners. Even their ‘new’ character, Frank Merriwell, dated back to 1900. Although Dime Novel sales were as off as they could be, the characters had considerable identification. (16) People may not have read them anymore, but they still had heard of them. More importantly, the sponsors, the advertisers who supported radio, had heard of these characters. By the time the networks were up and running, Street & Smith’s fare was everywhere.

(16) It wasn’t so much that people stopped reading Dime Novels for radio, but rather that the audience ‘aged out’ of them. At this point the Dime Novels were pegged as exclusively children’s literature—and not very well thought of children’s literature, at that. . Dime Novels weren’t particularly ‘nice’ and had a less than wonderful reputation with parents groups and educators. Although Frank Merriwell and Nick Carter were fairly clean living, quite a few Dime Novel heroes were along the lines of Jesse James. James is notable as a Dime Novel character, partially for its longevity, partially because it at least bore the name of a real life outlaw, but mostly for a high level of violence in fiction directed at children. At least in Dime Novels, Jesse James used to break off people’s arms and use the arms as weapons. And, after a time, they didn’t come up with any new material. Since right after the Civil War, generation after generation of 6 to 12 year old boys had become hooked on reading through Dime Novels. One could argue that the advent of the color funnies and films and radio were at that point eating the audience, however that isn’t the whole story. By the 1890s regular publishers were encroaching on this juvenile market and a much better class of children’s books had shown up. It was these better produced, more wholesome books, which had taken the biggest bite out of the Dime Novels

Street & Smith was all over the radio throughout radio’s Golden Age. The exposure seemed to have helped sales. (17) The firm replaced Munsey’s as the top publisher in the pulps. Had Street & Smith been solely in the Character Management business, they would have been sitting pretty. All during the 1930s, 1940s and early 1950s Street & Smith had at least two weekly network broadcast shows, a syndicated comic strip and a movie in production involving their properties. Even Disney couldn’t pull that off,

(17) The death of Frank Munsey in 1929 may have also been a factor. Munsey’s firm continued to operate without a real line of succession until it was finally liquidated in 1940. It started losing traction to Dell, Macfadden, Fawcett and Street & Smith during the intervening years.

And there was a feedback loop to it. During a broadcast of Street & Smith’s Detective Fiction Magazine show the announcer spontaneously decided to give himself a name, the Shadow. (18) The firm exploited this name by issuing a pulp with the same title. Eventually it led to the rival of the entire single character magazine genre. The success of the Shadow was soon followed by the launch of new character titles from Street & Smith, Doc Savage and the Avenger. In time, the Avenger followed the Shadow onto radio. As with Frank Merriwell and Nick Carter, the new heroes of Street & Smith pulps were corporate creations. The writers were nothing more than hands hired to work approved plots (often to match pre-done artwork.) Research was also often provided. That said, at least early on, both the Shadow and Doc Savage each had very talented writers behind them and both were largely handled by a sole writer. But these writers were given a lot of help. The Street & Smith fiction factory had re-geared for a new era.

(18) Supposedly this same announcer also gave Marilyn Monroe her stage name.

The Street & Smith method spread. An aspiring Detroit area radio syndicate set out to create a character who would attract a specific audience and hence a specific potential for sponsorship. Creating programs for specific audiences (and hence specific sponsors) was being contrived at the same time, resulting in the creation of the Soap Opera. (Women love love stories. Serials keep people coming back. A Soap Opera is a love story serial, involving female characters in situations women aspire to or with demographics they identify with.) It was similar thinking that led to the creation of this character who would attract a specific audience. The character the radio syndicate came up with was the Lone Ranger.

The Lone Ranger was a corporate contrivance from the get go. He was the result of a committee meeting, perhaps the best committee meeting ever. Although the Shadow was the narrator on the Street & Smith Detective Fiction radio program and then the star of his own pulp magazine, he wasn’t given his own radio show until the Lone Ranger became a big hit. And the Lone Ranger was a hit instantly. (19)

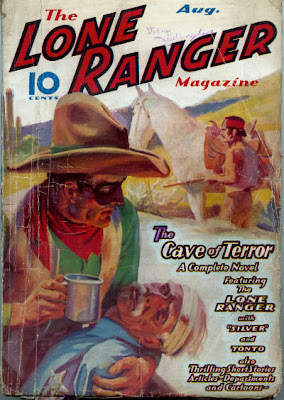

(19) The Lone Ranger went coast to coast in a blink. It was in comics strips and cereal boxes. It was one of the few heroes of any kind licensed to the pulp magazines. Within two years it was headed to the silver screen in the form of a movie serial series. It could be argued that the Lone Ranger, far more than the Shadow, was responsible for the sudden explosion of superheroes in all mediums. Before the firm that became DC Comics launched Superman, they were publishing a pulp magazine (shown) which licensed the Lone Ranger.

The Lone Ranger went through somewhat the same evolution Street & Smith had gone through about 20 years before. Interest in the Old West, no matter what you dress it up as, had started to wane. As the country became more urbanized, a preference for more modern and urban settings in adventure fiction started to materialize. Perhaps in recognition of this, or in response to the Shadow’s sudden popularity, the people behind the Lone Ranger came up with a modern version, the Green Hornet.

Although the Green Hornet and the Shadow are very similar characters, they were intended for very different audiences. At least on radio, the Shadow was a science fiction with horror elements program, primarily targeted at adults. The Green Hornet was the Lone Ranger in a car, never straying into the fantastic. Street & Smith’s approach was to just do their best to entertain the audience and count on that to attract sponsors. Ported in from the Dime Novels was a certain degree of the fantastic and relentless bloodshed. That was the draw. The Green Hornet, by contrast, never deliberately killed anyone or did anything which might offend sponsors wanting to reach a mid-day audience of twelve-year old boys—and their moms. It is a distinction in approaches which we see to this day.

By the late 1930s Character Management as a business function had been thoroughly fleshed out. And Street & Smith became the largest firm mostly in this field. By this I mean that they were making money off their characters mostly through licensing them to other mediums. This could also be said of DC Comics which was making more money off of Superman appearing on the radio, in syndicated comic strips and movie cartoons (and hawking goods) than they made off him in the comic books. But DC Comics was still making a lot of money off the comic books. In contrast, by 1940 Street & Smith’s pulps have started a slide of epic proportions. Once the war hit, paper shortages and other factors created a death spiral for the entire pulp industry. The powers at Street & Smith decided that the downturn was permanent and started an exit. By war’s end, pulp magazines were no longer a part of Street & Smith’s future.

By the late 1930s Character Management as a business function had been thoroughly fleshed out. And Street & Smith became the largest firm mostly in this field. By this I mean that they were making money off their characters mostly through licensing them to other mediums. This could also be said of DC Comics which was making more money off of Superman appearing on the radio, in syndicated comic strips and movie cartoons (and hawking goods) than they made off him in the comic books. But DC Comics was still making a lot of money off the comic books. In contrast, by 1940 Street & Smith’s pulps have started a slide of epic proportions. Once the war hit, paper shortages and other factors created a death spiral for the entire pulp industry. The powers at Street & Smith decided that the downturn was permanent and started an exit. By war’s end, pulp magazines were no longer a part of Street & Smith’s future.

Sadly, Street & Smith wound up not having much of a future, period. This would have never happened today. Today, you could not pry even a minor character like Dewey Duck away from Walt Disney, for any amount of money. In fact, it is one of the Disney company’s objectives to get Andy Panda (a character few have heard of) away from Walter Lantz. Today no one lets characters go and it is highly unlikely that any character will ever fall into the public domain again.

Street & Smith’s 1953 exit of its properties marks the last real giveaway of the Character Management era. Sometimes “Good Will” items are hard to value. At the time Street & Smith’s core business was publishing, not character management. What licensed properties it had were primarily tied to radio, a medium which also seemed to be in decline. Couple this with pulp magazines being in decline also and you can see how it might be thought that there wasn’t much future value in their character properties. As some form of proof, a late effort to use these characters in comic books was less than a raving success.

There were other factors at play, the most important of which dealt with the longevity of Street & Smith as a business. The firm had been around since 1850. By 1953 there had been several generations of heirs, not all of whom had been interested in running a publishing company. The last heirs simply wanted their inheritance in cash. For much the same reason that Iran and North Korea seek to develop nuclear weapons, Street & Smith had sunk the majority of its post 1930 cash into the launch of a woman’s magazine. When it comes to little pulp magazine firms, that’s usually the end of the story. But Street & Smith had been successful in this objective and by 1953 their girl’s slick Mademoiselle was responsible for 53% of the firm’s total income. They also had a paperback and hard back division along with some prominent sports magazines. It was these things that they were out to sell. As for the pulp magazines or their attached characters, they were sold for their current value as magazines. At that point, not much.

It would have been a different story had they been solely in the Character Management field, an industry they created. Although the Shadow magazine had dwindled down to digest size and radio was clearly a fading medium, it had been a top program. Only a few years before, a second Shadow movie serial had done very well. When it finally did fade from radio, the Shadow had been on the air for eighteen plus years. And there was a contract to do a TV show. (It did air, but I am not sure how well it did. It seems to have aired after the sale of the character to Love Romances Inc.) As it should turn out, the downturn in comic books was temporary. (There were other reasons for getting out of comic books at this point. Street & Smith was not the only firm to exit the comic book field right then.) Even if they weren’t doing Superman numbers, the Shadow had been far more successful in comic books than most characters. They even had a hit character called Supersnipe, which they had originated in the comic books. Nick Carter, who was no longer in any Street & Smith publication, had a radio program late in the era, as did Frank Merriwell, who also had a syndicated comic strip and movie serial. With westerns being all the rage on television, having the rights to several thousand short stories in the genre as well as the rights to the image and name of Buffalo Bill Cody could have been considered assets. Obviously these assets had some long term staying power.

But no. They let the whole lot go for one year’s profit on half a dozen pulp digests.

Oddly, the Shadow and all of these other properties did wind up in the hands of a fashion magazine publisher anyway. The firm Street & Smith sold the Shadow and a bunch of Love digests to, Love Romances Inc, was itself acquired shortly afterward by girl’s slick monopoly Conde Nast. Today the Conde Nast historian earns his keep pimping out the Shadow and Doc Savage to movie firms. Unlike Street & Smith, Conde Nast has no intention of ever letting these properties go or slide out of copyright.

Walt Disney, of course, took the field to a new level. Not only did he actively market his characters, he was the first to come up with an actual immersive experience. Although there were theme parks before Disney came up with Disneyland, most of them had ‘imitation of Coney Island’ as their real theme. Or they had Santa Claus of Paul Bunyan walking about. Which brings us full circle.

***

Another posting, another typographical nightmare. I'm not sure if the whole imbedded footnotes idea is a good one or not. In any case, I hope to clean this up before it gets posted onto the website.

I had no idea Wild Bill Hickok had such pull as a fictional character until I started fishing for images of him. There's a whole posting to be done on the subject of superheroes in fiction who were scumbags in real life. Wild Bill and Jesse James lead the list.

There was a bit of late breaking news about the Kit Kat Clock people being sued by the Felix the Cat people which I ran across as I was image fishing. I found the whole thing strange, since both products are seeming rip offs of Krazy Kat. Oh well...

By the way, if you do operate a campsite out there, the Yogi Bear people have a whole package to transform your park into their theme. It's quite comprehensive. At one time this operation was actually a part of the HB animation firm. Or you can just do Paul Bunyan and call it a day.

I am going to do something much shorter next time.

No comments:

Post a Comment