One of the remarkable features of the pulp magazine industry

is how few failures there were amongst the publishers plying the trade. In general, publishing is a rather high die

off business. In the present, where the

cost of production has dropped significantly, few publications or imprints make

it to their third birthday. Even well-funded

efforts, such as a sports genre daily called The National, have wound up

spitting the bit.

As we have stated before, the future of the magazine as a

medium itself is now in doubt. Distribution houses have been evaporating. Bookstores

and bookstore chains are imploding with the frequency of soap bubbles. Newsstands

have disappeared. Supermarket checkout counters now deploy the space once

slated for magazines to video disks of last season’s movie hits and candy. Drug

store chains have followed suit, many relegating all printed materials to one four-foot

square booth thing somewhere near the window with the anti-freeze. The world of

paper is drying up and blowing away before our very eyes.

What’s the hottest thing in the printed world right now?

Coloring Books. Coloring Books FOR ADULTS. Previous to that it was a number

game from Japan, of all places. If you do find magazines of any kind at this

point, the majority of them are going to be pulpwood activity books—word finds,

crosswords, astrology. So pulp does linger. The format lingers. Its economics

linger.

If anything, pulp is having something of a revival. Much

of this is taking place at the dollar stores and the majority of it has been in

the activity book category. Pulp has

always done well in low brow retail. It’s the place the industry was born. It

matriculated out from the train stalls, the general stores, pool halls, gas

stations and lending libraries. It was the gas stations and thrift stores which

first gave us the paperbacks, not the supermarkets which they were supposedly

designed for. So far actual literature has yet to make a showing in dollar

store land, but it is around the corner.

The dollar stores are here for good. (Or until Trump starts

a trade war.) (Or until things become wonderful again.) Presently the dollar stores have been serving as the lowest form

of hard back book remaindering, the last gasp sales venues for fired college

football coach biographies, faded diet fads and discredited self-help twaddle. But

there is only so much catastrophic loss hard bound inventory out there. And even

in the dollar stores, there are some things that just won’t fly. (Failed

predictions of the world’s death at the hands of Aztec calendars comes to

mind.)

Coming in like cottonwoods are the dollar versions of

dictionaries and atlases. We are also seeing a smattering of public domain

writings, classics writ small and on as cheap of paper as the producer can get

away with. Sensation and escapist lit seem just around the corner, probably

starting with Wells and Verne. That’s how it always starts in any new venue.

Any look around a dollar store is a tour of old names.

Brillo Pads, Mister Plumber, Necco Wafers, Malt-O-Meal and Pepsodent have all

made dollar store come-backs. With the exception of Pepsodent, I am not sure if

these new incarnations are the same products that they once were. Some clearly

are not. Malt-O-Meal used to be a product itself, not merely a brand name stuck

on mini sized knock off versions of breakfast cereal.

You can see why they do it. The dollar store environment is

a maze of mostly anonymous, possibly shoddy products. Having any sort of

recognizable name helps bestow a claim of being not so fly by night and perhaps

not so shoddy. It also helps to have a title that people already remember, even

if its relationship to the product being offered is rather distant.

It's a rather old ploy. We saw it in the pulps often. Argosy

turned into several different types of magazine before it gave up the ghost.

And in revival, it has been a haughty lit magazine—the exact opposite of its

heyday. In the end, the title was all the producer was willing to hang onto,

simply because it was felt that Argosy was a name people remembered as at least

a magazine. We first saw this Malt-O-Meal transition in a long running title

called Pep.

This is Pep.

Pep is porn. At least in its 1927 debut, Pep is a typical

example of a dirty magazine of the time.

There’s a bit more to Pep, which is why I am writing about

it. In this series we will be tracking various pulp idioms, genres, titles,

characters, writers and publishers as they matriculate through the pulp medium

and into other spectrums of the popular culture universe. It’s a fairly broad

topic, the “so what” of pulp magazine history. We’re starting with trademarks

and Pep is a fine example.

To most of us, the word ‘Pep’ doesn’t mean anything. Many

may have last run into this buzz word in high school, in the context of a Pep

Rally. There was even a Pep breakfast cereal at one time.

The cereal pre-dated Pep magazine by four years. Pep the

cereal was the Kellogg’s version of Wheaties—so alike that they could not be

distinguished without the box. In the case of the cereal, the Pep name is taken

from patent medicine claims, as in a restoration of vitality. It will make you

peppy. Pep’s only specifically touted product claim was its mild laxative

action. Note that the identical Wheaties never made this claim. Instead

Wheaties stuck athletes on their boxes. Pep never was much of a competitor and

pooped out in 1978, leaving wheat flakes category glory to Wheaties alone.

Concurrent with Pep’s introduction as an actual product was

its appearance as a genre descriptor on the covers of various magazines. Again

the word’s popular take comes from patent medicine claims, usually for items

meant to act as stimulants. In this sense, Pep means stimulating in a not so

gradual way. It is an enjoyable shock to the system.

Keep your minds straight in the gutter, because that is

exactly where the publisher of Pep is coming from.

There are other product buzz words similar to Pep such as

Vim and Vigor. That’s not what the publisher of Pep or the other pulps with Pep

or Peppy on their masthead are out to represent. The word had migrated a bit.

By the time our aspiring smut merchant hit upon Pep, the term had become

attached to college sports—as in Pep Rally. In pulp smut terms Pep and Peppy

meant a college setting.

The format, smut + humor, was a standard even before Pep

rolled off the press. The smut + humor + college formula may have been Pep’s

only slight distinction. If it was unique, it wasn’t unique enough. Within

three issues Pep was done… at least as smut. Pep itself went on to transition through two

other formats until finally passing on in 1987. That is a great run for any publication title

or the trademark of a product. And about all you can say for Pep is that it

remained printed material, a regularly produced periodical, for the majority of

its run. It didn’t go onto become a

video game or a movie. At worst it became an irregularly produced reprint

digest.

Over time Pep developed value as a trademark. Sticking the

title Pep on a magazine assured its distribution. It was identified as a going

concern, a known quantity by retailers, distributors and, one imagines, the

public. That’s pretty good for a trademark which was quickly antiquated and

somewhat oblique in meaning. By the time ‘Pep’ ran out of value, other

magazines with sleaze buzz such as Breezy, Spicy, Saucy and Parisian had been

done for decades.

I guess the letdown is in what Pep actually was. Mostly it

was erratic. It was an also ran, a trend chaser, a knock off of the latest fad

only a few months too late. It also managed to never have much of a distinct

style of its own, other than the style of its sister magazines. Except for a

brief golden age, it is never a progenitor of anything, but rather a second

helping left over version of whatever its publisher is offering in other more

targeted magazines. This is its only consistency—and it changed genres and

formats often.

Even in 1927 it is the last sister of a fleet of three or

four other smut titles put out by the same publisher. Then as now, smut could

be sorted into low, medium and high settings. The breadth of the market was in

what we today call soft core porn. (Full frontal nudity sans the models giving

us a biology lesson.) Hard core porn existed and was probably peddled in the

same places where Pep could initially be found.

Pep is what is commonly called an under the counter

magazine. (Meaning it’s smut.) Such magazines used taverns, pool halls,

billiards parlors and other stray men gathering places as their primary outlets

of distribution. By 1929 the majority of under the counter magazines had taken

the form of pulp magazines. There are two to twelve pages of litho stock photos

of naked women sandwiched in the middle of a magazine largely comprised of

newsprint.

It’s a high mark-up impulse buy item. Beyond being

profitable, it’s also something of a draw to the retailer—bringing in men who

might just want to look at the magazine, but are probably going to buy

something else. By the time Pep appears, distribution had spread to barber

shops and liquor stores. (And to clandestine bookstores.) Even at this date the

appeal of these items was well established. Pep was nothing new, even in its

college girls gone wild niche.

The smut field was lucrative, however it was technically

illegal. And it’s all mobbed up. Which makes our publisher something of an

adjunct mobster himself. In the case of Pep and porn in general, these are

Jewish mobsters. We covered the mechanisms by which these magazines were

distributed in a previous post. In the book It’s A Man’s World, they

cover the peddling and production of the naughty pictures themselves, which seems

to have been an enterprise dominated by Orientals. The mob at this point was an all ethnic

American racket.

I am not sure how far Pep’s original publisher stayed on. (I

am lacking a copy of an early issue.) The person who publishes a porn magazine

is usually in possession of little more than pre-production assets—the physical

tools that are required to lay out a magazine for production. The rest of it is know-how and connections. A

lot of publishers started out in porn and then went into other things.

Although porn magazines are lucrative on a per unit basis,

they have a sales ceiling. It was also a

crowded market, with a lot of money flying out the door up front. In most publishing, the retailer and the

publisher essentially split the profits, with the distributor acting as a

banker to the tune of about 15%. In the

under the counter trade, the retailer makes 75%. (The retailer is far more likely to be thrown

in jail.) In order to increase their margins, make found money off of previous

expenses, many a porn publisher hit upon a simple trick—yank the girlie

pictures out and sell it as another magazine on the general market.

Around about issue four this is what Pep became. At the

time, the real money was in producing pulp magazines in the broader market. As

a general circulation magazine, Pep’s contents became the shovel-ware container

for editorial culled from smut magazines. And it may have been an amalgamation

from several publishers. It is as recycled smut paddling that Pep gains its

traction on newsstands.

It wasn’t entirely an innovation. The entire Culture Publications genre line

published in both smut and non-smut versions. From what I can tell, Pep was this publisher’s

only general pulp and its only purpose is to get greater utility out of

material meant to pad out porn. If anything, Pep is noteworthy for not being

all that careful about pruning the text for general taste.

There was an accepted market segment for something like Pep

in the general pulp magazine universe. I call it Flapper Fiction. To be short, it is unsentimental and graphic

about the subject of sex—and sex is its only subject. This trend flourished

from the late 1900s to the mid 1920s, launching dozens of titles. The flagships

of Flapper Fiction were Breezy Stories, Snappy Stories and the Smart Set. At

the height of the literary food chain of this niche, it’s quasi-feminist, the

Flapper backlash against Suffragette asexuality, the retail version of a post

WWI literary trend. By the time Pep shows up, the once twice monthly Flapper

Fiction titles are now coming out eight to ten times a year. So the trend is

well past its height when Pep enters the mix.

Besides a desire to recycle, Pep’s publisher may have had

another, more macroeconomic reason for shedding its porn trappings. During the

1920s nudity in print was everywhere. The film fan magazines often featured

naked pictorials of movie starlets. Quite a few respectable titles ran art

nudes as a matter of course. To actually qualify as porn, a publisher really

had to “do something”. (And Pep’s publisher is not an art guy.) Then the stock

market fell apart and the party was over. The girls put their clothes on,

banishing public nudity forevermore. A great depression was on. Suddenly no one

has 25 cents for your porn magazines. This possibly explains Pep’s very short

run as porn.

As Flapper Fiction, Pep is operating on an extremely low

wrung. If you gutted Hustler of the pictures, it would still be a vulgar

magazine. Pep is no better than that. Unlike Hustler, which is patterned after

lifestyle magazines, Pep is a fiction anthology. It’s short stories and

vignettes—the type of stuff that padded out porn at the time. As with porn, many of the male slanting titles

in this genre packaged themselves along theme lines, usually as humor. At least

on the covers, Pep is doing the same thing. It’s fun, funny sex stories.

The covers were one thing, the stories were another. (Pep

was not alone in this, but the covers seldom had any relationship to the

stories found inside.) Although packaged like Snappy or Film Fun or Judge, Pep

lacked any whiff of humor in its stories. Whatever smut the editorial was being

clipped from was not the fun smut. There was a theme to the stories, which I

will explain briefly: (A) one party has a sudden/urgent need for sexual

activity; (B) the expression this of desire in some way greatly inconveniences

the prospective sex partner; (C) somehow the inconvenience is either surmounted

or endured. To its credit, it’s not violent. These aren’t rape fantasies. At

best the construction is similar to a screwball comedy, only without the jokes,

a farce without a point. But that may be cutting it too much credit.

Other Flapper Fiction magazines, regardless of their place

on the spectrum, were not quite as hide bound to a formula as Pep was. There

are occasional gems descended in from other genres which saw print as Flapper

Fiction. At one time there was a short-lived anthology focus on airships. Stick

a zeppelin in a story and there were three magazines which would gladly feature

it. No sooner did these anthology titles open shop, when bad things started

happening to airships. First they crashed in Chicago, killing dozens on the

ground. Then they were banned from the skies in all major cities. Then they

were banned from crossing the airspace of any populated area. (All of this

before the crash of the Hindenburg.) Suddenly the whole zeppelin thing isn’t so

attractive and the anthologies folded shop. So what does a writer do with the

story he wrote for Zeppelin Stories? What does the editor do with the story he

bought for the never to be published next issue? Toss in a naked girl and stick

it in a smut pulp. A progression of offbeat or off trend stories accounted for

what literary quality occasionally landed in the later stage Flapper Fiction

magazines. It may have been part of the draw. But not with Pep. Pep’s stuff was

written as porn and illustrated with goofy cartoony nipple showing

illustrations, entirely without variation, issue after issue.

The formula seems to have done rather well. At a time when

Breezy and Young’s Magazine have amalgamated and Smart Set has folded shop, Pep

is coming out monthly like clockwork. By 1932 Pep is part of a non-genre fleet

of pulp magazines put out by the same publisher. Pep’s sister publications

include:

Broadway Nights:

A low end salacious romance title, which did double duty covering New York

Theater District gossip. Broadway Nights seems to have been patterned after a

previous incarnation of the slick pulp Blue

Book. Unlike Blue Book it touts the

big shows without a whiff of criticism and mentions some not so big shows as if

they were big shows. Almost reads as promotion copy, which the editorial may

have been cribbed from. These departments sandwich a fiction anthology chock

full of chorus girls being chased by lechers and a center folio of litho

featuring women in racy evening wear. Flapper Fiction had an appeal to both

sexes and this title was out to sell sex in a rarefied setting. Like Pep it was

started in the late 1920s. By 1935 it was sliding towards themed romance. In

its later incarnations, it was themed smut.

Paris Frolics:

The term ‘Paris’ in pulp land means nudity. The promotion ad in the April 1932

issue of Pep makes Paris Frolics out to be a wild orgy in print form. It was started

in 1928 as Real Story, an under the counter pulp playing off the True

Confessions trend. The idea was for it to be a photo-illustrated version of a

Penthouse letters section. In practice, it was first person smutty accounts

surrounding a folio of nude photos, none of which bore any relationship to each

other. As Paris Frolics it was rebound returned issues of other magazines, all

wrapped in a cover whose illustration was repurposed from a previous year’s

issue of Pep.

Spicy Stories:

Not to be confused with Spicy Magazine or Spicy or Spicy Western or Spicy

Adventure or any other Spice-like title. Spicy and Snappy were code words

appropriated by many of the late Flapper Fiction titles. Spicy Stories was a

late comer to the Flapper Fiction trend and represents everything that went

wrong with the high minded ideal of sex without sentimentality. Even as late as

1935 it still has a department devoted to giving advice to aspiring Flappers.

(Any stray Flapper at that point would be cresting 30.) Spicy was essentially a

unisex version of Breezy Stories, spritzed with rotogravure printed art nudes.

Spicy Stories, Breezy Stories and Young’s Magazine were the top of the heap in

the Flapper Fiction field during its later stages.

By 1935 Pep’s line up of sister publications had changed somewhat.

Broadway Nights and Paris Frolics were gone. Added in their place were Snappy (not to be confused with Snappy

Stories or Snappy Magazine), La Paree,

Gay Broadway (perhaps a retitle of

Broadway Nights) and Gay Parisienne

(sic). Of the newcomers to the sisterhood, the oddly titled Gay Parisienne is the most successful,

equal in production quality to Spicy

Stories. La Paree is a smut

magazine and shares some departments with Pep. Most of these new titles existed

prior to 1935 and their inclusion with Pep perhaps is representative of some

amalgamation of publishing interests.

Perhaps ‘amalgamation’ is too dignified of a word. I could

go into gymnastics attempting to tell you who owns these various publications,

but the exercise is pointless. At the time it was not in the publisher’s

interest to tell you who owned his magazines, since some of them were illegal.

I can’t even tell you if Pep Stories is exactly the same

magazine as Pep! the porn magazine—although it does continue the numbering. I

can tell you who published Breezy Stories and Young’s Magazine. That guy had a

snazzy four story building off of Washington Square in New York. I can even

tell you who put out the other Spicy titles, such as Spicy Detective. (At one

time that guy did own Pep.) As for the producers of Pep and its sisters, what I

can say with certainty is that they are as thick as thieves. All of these dozens

of imprints are owned by a small circle of people involved in various forms of

under the counter and newsstand distribution networks and all operating out of

the same building. Krypton has not exploded yet, so it’s hard to tell which

chunks are about to become whose.

Then Krypton explodes. One of the guys in the building has

discovered Superman, becoming a

teen-aged mutant ninja millionaire. He’s got comics to churn out, by the box

car. Soon everybody in the building wants to get into comic books. Nothing like

a big pile of money to break up a band of thieves. Suddenly everyone becomes

proprietary about who owns what. The chunks from Krypton are being claimed. Or

so the story goes.

I chose Pep because it is a fine example of all three types

of pulp matriculation. The first type is Direct Transfer. Pep is a magazine

which changes formats. It goes from slick porn to pulp flapper fiction to

something else. There is a clear chain of custody. The magazine continues to

publish regularly despite the shift in contents or change in ownership.

Pep could also be, in its early stage, an example of

Snatching. Pulp publishers thought nothing of snatching each other’s titles,

sometimes concurrently. Thus we see the proliferation of the word ‘Snappy’ on

very similar magazines owned by different publishers. And if True Crime

magazine should suddenly stop printing for a month or two, the title became

fair game for another publisher to snappy up. No one bothered suing anyone for

trademark infringement because no one ever bothered to trademark anything to

begin with. Or so the theory goes. Although true on the periphery, I believe snatching

is largely a myth. Per the Snatching

mechanism the Slade brothers let their pal Donny filch the Pep porn title for

use in a new magazine which recycled editorial from other porn magazines—and

didn’t feel too put out when Pep became a sustainable hit in the newsstand

market. That’s a bit too charitable for mobsters—even ones in the prissy porn

racket.

The final matriculation method is Sideswiping. This is where

a comic book or a digest series or a slick magazine simply takes a pulp title.

9 times out of 10 it’s the same publisher who owns both entities. The American

Mercury started paper-backing popular series novels using its imprint. Half of

all of the early non smut digests were novels previously published in pulp

magazines. Digest king Hillman

published Crime Detective as both a pulp and a comic book. Venerable pulp

producer Fiction House produced both pulp Planet Stories and comic Planet

Comics, twin science fiction anthologies. Just as some Dime Novels had

transitioned into Pulp magazines, some pulp titles converted to comic books.

Rare was the instance when a pulp produced by one party became a comic book

produced by another, as was the case with the long-lived Action Stories and

Action Comics.

Pulp magazines were the publishing disruptor of the 1890s.

The flagship Argosy was published weekly for a time, selling in the millions.

Massive competition followed, leading to the rise of identifiable genres of

fiction, such as romance, western, fantasy, detective, horror and its evil twin

science fiction. Directed largely at an adult audience, it spread an appetite

for escapism to the masses. Vast printing batteries and binderies emerged to

service this industry, mostly centered in New York. The boom went on unabated

for thirty years. Movies took away some of the pulp audience, The rise of radio

in the early 30s killed magazines and newspapers in general. Then the

Depression hit.

Had the Depression not hit, Pulp magazines would have been

technologically replaced by the early 1930s. A form of press, known as photo

offset had been introduced in the 1920s. These presses allowed for shorter runs

and less expensive set up and had much finer line quality for pictures than the

linotype driven pulp batteries. But the Depression did hit and no one was

buying printing presses, much less photo offset types. And in the gear up for

war, the supplies for the photo offset process are being diverted elsewhere. If

economic conditions were just a tad better, the Pulp and Comic Book landscape

would have been far different, with one form vanishing sooner and the other

form perhaps never being born.

Both Pulps and Comic Books were offshoot products of press

batteries with plenty of spare capacity. Pulps could be produced entirely in

house at any typical magazine battery. The only special substitution involved

seeding in inferior interior stock. They’re not rare, and, in the Depression,

most of them are willing to extend credit to even the dodgiest of publishers. Comic Books, by contrast, involved several

different presses, very few of which had the capacity to produce the entire

product in house. The interiors are run

off of four color web presses. They are newspaper presses set up to run

different cycles of colors on very soft absorbent stock, primarily intended to

produce the Sunday comics section. At about the same time as the pulp batteries

are first sprouting up, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst and his

competitors are setting up these presses like Johnny Appleseed all throughout

the country. Unlike the pulp batteries, they are not centrally located and they

are not all of the same quality. Being newspaper presses set up for the production

of newspaper sections, they do not house binderies. And if you want the thing

assembled with a nice slick cover, you have to go back to the pulp batteries. A

lot of moving of materials goes on before the first comic book is produced.

And a lot of things have to take place before that. Someone

has to plot out where the color cycles are to be placed. A separate plate for

each color cycle needs to be made—and there’s an art to this. If the plate is

wrong or the print cycle is too fast or too slow, the red on Superman’s cape

becomes a free-floating red blotch running askew a cloud bank. Close Registry,

the art of putting colored fields within the bounds of black and white borders,

is expensive and occasionally hap-hazard. And not all presses or paper types

have the same color pallet. While the guy who owns the web press is just as

free with the easy payment terms as our pulp battery owners, the people who

supply the color separations and plates are cash on the barrelhead types. You

need to buy the paper and the inks and the plates before our web press guy is

going to even think of running the job. It’s complicated. It sucks money. And

to do it economically, the process requires a three-month lead time.

That’s a three-month train to produce one issue. If you want

to produce on anything other than a quarterly basis, you have to put three

issues in the pipeline. That’s daunting. Suppose no one likes your comic book?

You don’t just get one flop, you get four.

It appears that the publisher of Pep is not entirely aware

of all of the risks involved. What he does know is that two of the people he

used to share office space with are now doing quite well in comic books. He

wants some of that good, good Superman money. So he plunges right in.

Sort of. He tips a toe in. His first comic is Top Notch. As

a title for a pulp magazine, Top Notch dates back to the Dime Novel era. But this is an incident of Snatching. Our

intrepid publisher previously put out two pulp magazines (or one pulp magazine

which switch hit between Western and Sports genres every other issue) called

Top Notch. With Top Notch we see in microcosm the mistakes this publisher would

make early on.

By 1939, the year of Top Notch’s debut, comic books have

become a standardized product. They are 64 pages with set dimensions. Like the

Sunday Funnies, whose presses they are printed on, they are in full color. Top

Notch is not. Top Notch is tinted, in single spot color—and only half tinted at

that. It is half black and white. Up against Superman and Walt Disney, Top

Notch is not going to do very well. As you will see, the contents didn’t help

either. Let’s call it a proof of concept.

By issue two, Top Notch is in full color. And it’s time to

launch another title, Blue Ribbon. There was a Blue Ribbon pulp as there had

been a Blue Ribbon Dime Novel/Story Paper series, but I am not sure the

publisher had legit dibs on any of them. Blue Ribbon as a trademark for

anything was usually favored by producers of generic food stuffs, following the

idiom that if you don’t have anything special to peddle, pretend you’ve won

some sort of award for it.

Blue Ribbon is also in full color. End of praise. Although

the brain trust at MLJ has ponied up for color, they’ve kept the same printer.

(Perhaps due to his fine credit terms.) The problem here is that this printer

is not all that good at close color registry. And he has a strange color

pallet. The favored murky greens and murky blues used are often way off target.

MLJ is not letting these quality issues get in its way.

Month three of the venture sees the introduction of Pep Comics. Pep was at this point was the only non-smut

smut padding magazine left. (It would be ten years before there was another

title launched in the genre.) The entire Flapper Fiction field had become a one

publisher show, dominated by Courtland Young’s successor Phil Painter. Having

Pep leave a dwindling and monopolized field with its continuous mail permit

intact seems the reason for its conversion into a comic book.

A comic book is born.

Pep is a hit from the start. Or it’s a hit compared to Top Notch and Blue Ribbon, which are certifiable dogs.

Pep is a hit from the start. Or it’s a hit compared to Top Notch and Blue Ribbon, which are certifiable dogs.

As Golden Age superheroes go, the Shield is typical. He’s a

discount Superman wearing the flag. (He’s sort of a combination of The Flash

and Spider-Man, but the outfit is his real distinction.) As old hat as covering

your cover guy in the flag may seem, the Shield is the first comic book hero to

pull it off. He’s the original.

Mandrake the Magician was an extremely popular character in

the comics section. At the time that this was released, Mandrake was starring

in movie serials and on the radio. Visually Top Notch’s Wizard is a Xerox of

Mandrake, only in a white tux. Over time, the character becomes more of a

psychic chemist plutocrat immortal, but early on the Wizard is a clear rip-off

of Mandrake, and not a well done one at that.

Rin-Tin-Tin was a dog rescued from a WWI battlefield. The

German Shepard and its namesakes appeared in silent movies during the 1920s. By

the time Blue Ribbon appears, the dog’s fame was long passed its apex. Making

your headliner a rip off of a famous dog, probably only known to the parents of

the potential consumer, is a dubious move. Given the sudden shift of focus

after four issues, the concept seems to have proven a dog.

So our Pep guy (MLJ Publications) is off to a spotty start.

Worse, someone soon rips off his one good idea.

Lawyers are contacted and MLJ makes Captain America change

his shield from the pointed one he first appeared with to the round one we see

him with today.

It should be said that the people at MLJ did not come up

with any of the characters in their first three issues. Rather these characters

were thought up at art shops. Factory-like studios had sprung up to service the

comic book industry. All the MLJ guys do is walk in, order up a number of pages

and pay the lady on the way out. As with many emerging crafts, there were tiers

of prices for tiers of quality. For the first issues of Top Notch and Blue

Ribbon, MLJ is paying top tier money for the covers, second tier money for the

first feature and bottom shelf for everything else. By the time Pep rolls

around, it’s second tier money for the cover and bottom tier for everything

else. Within six months the art budget degenerates from there.

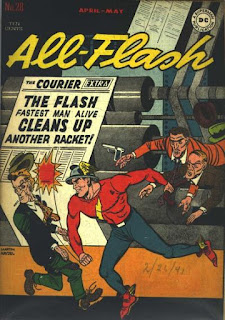

With Pep, at least, they had some luck. MLJ chanced into some young artists who were fast developing and under-priced. The cover above is by Irv Novick with a little help from the shop hands he works with.

With Pep, at least, they had some luck. MLJ chanced into some young artists who were fast developing and under-priced. The cover above is by Irv Novick with a little help from the shop hands he works with.

This is Irv Novick without much help. Novick also does

interiors and gets better at his craft in a hurry. They also chanced onto Irwin

Hassan, who is fantastic right off the bat. Hassan will depart for syndicated

comic strip work shortly. Novick becomes their early mainstay, but there is

only so much work he can do. The drop off in art quality effects Pep Comics

less than it does Blue Ribbon and Top Notch.

This Top Notch cover is fairly typical. The Wizard has

dropped the tuxedo in favor of Superman’s cast-offs. This is as close to

blowing your nose on paper and hoping to make a profit as it gets. MLJ is

hardly the only low quality producer in the field, but they are the most

comprehensively shoddy.

Despite this, Pep Comics is a certifiable hit, a consistent

top 25 selling comic book. It doesn’t touch the numbers that Superman or

Captain Marvel or Batman or Wonder Woman or even Captain America hit, but it is

on a par with far better produced fare. And Pep Comics is not that different

that the languishing Top Notch and Blue Ribbon. All three comics are general

purpose anthologies, sprayed with the usual assortment of stereotypical

features: a superhero or two, a space guy, a jungle guy, a detective guy, a

magic guy, a cowboy, a boy inventor, a military guy--all padded out by the post

office required text feature and a few gag pages. There’s very little variance

between the magazines.

There is sometimes very little variance between MLJ’s

superheroes. Shield, Comet and Steel Sterling all have effectively the same

origin. All three are mad scientists who have invented a chemical which will

give them super powers. Shield smears the stuff all over his body and then

seals it in with a specially designed suit (to keep it from evaporating). Steel

Sterling smears the stuff all over his body and then JUMPS INTO A VAT OF MOLTEN

STEEL to (I guess) vulcanize it into his skin. And Comet drills holes in his

head, injecting the stuff directly into his brain. Steel Sterling (billed as

the Man of Steel) and Shield wind up with nearly identical powers, whereas

Comet is endowed with ‘dissolvo-vision’. Black Hood and Black Jack are both

police officers in their working hours, both normal dudes in costumes and are

both wearing nearly identical uniforms. It’s a stunning degree of conformity

amongst characters who are not knock offs of each other.

Many of MLJ’s other heroes are steals of other publishers’

properties. Mister Justice is a swipe of the Spectre and Red Rube is a swipe of

Captain Marvel and Captain Commando is a swipe of Newsboy Legion and Fireball

is a swipe of Human Torch. Or theft with a twist. The Wizard manages to loot

Lee Falk twice, stealing the Phantom’s backstory and Mandrake’s powers. Kalthar

is Tarzan only with the ability to grow into a giant. Captain Flag pillages

Tarzan again, substituting an eagle for apes and then using it as a backstory

for a Captain America swipe. All of this said, this is not atypical comic book

publisher behavior.

How much planning or deliberation went into this is anyone’s

guess. My thinking is that a lot of MLJ’s features were initially shopped and

rejected elsewhere. The M and the L in the MLJ partnership are both accountants

and cost control seems to be the partnership’s focus. MLJ is an experiment in

how little money you can spend and attract a profitable level of circulation.

To defend the MLJ partners, they have been dealt the dummy

bridge hand in the vast world of comic books. The M in MLJ is the lead accountant for the publisher of

Captain America. That publisher also doubles as MLJ’s distributor. (The only

other reliable distributer MLJ can turn to is the publisher of Superman.) The L

in MLJ used to be business partners with Captain America’s publisher and they

have had a very nasty falling out. So MLJ’s lead partner is a spy and its

distributor is out to destroy it. No wonder their one good idea got spirited

off. The firm is completely transparent to their competition. Moreover, they

have no money. L has connections in printing and a credit line. J is the idea

man. There is no cushion here. MLJ has to make a profit from the get go.

Making matters worse, MLJ is a little late to the party.

MLJ’s two former pals from the porn industry, the publisher of Superman and the

publisher of Captain America, are off to a fine running start. Heavy hitters

are now wading into the comic book waters, in the form of the publishers of

Mechanics Illustrated and the Saturday Evening Post. Pulp heavyweight Street &

Smith is launching a line of comics, porting in household names The Shadow and

Doc Savage with them. Swooping in are other, more veteran pulp producers, A.A.

Wyn, Thrilling Group and Fiction House. The art studios themselves are getting

into the act, launching their own titles. Coalitions of comics creatives, some

of the best artists and writers, are forming for profit communes to issue

comics on their own. All of two web presses are capable of producing the entire

comic book product in house—one is owned by Superman and the other is about to

become tied up with a deal to produce comic books about Walt Disney, Looney

Toons and every animated character anyone can name. Given how hotly contested

the resources MLJ needs are, it’s something of a wonder they can produce at

all.

OK. Sometimes MLJ pooped on paper to an inexcusable degree. Fiction

House and Big Shot were just as poor as MLJ and those firms put out gorgeous

comic books. During the Golden Age of comic books the correlation between high

production standards and increased sales was not widely subscribed to. No one

in comic books was Leonardo Da Vinci or even Norman Rockwell. Superman started

out rather crudely rendered and improved very gradually. Batman was

artistically on a par with Dick Tracy. Wonder Woman was illustrated by someone

doing a second rate imitation of Fritzi Ritz. The Flash, a character who held

down the lead slots on three comics a month, was seemingly drawn by an eight

year old with a butter knife. Those comics sold in the millions. Making

magazines for 12 year olds is a hit or miss business. MLJ’s commitment to doing

things on the cheap is understandable if not entirely laudable.

Pep’s initial success cannot rationally be attributed to

production standards nor its formula. An examination of its feature mix does

reveal certain novel twists. Sans the uniform, the Shield is the Golden Age

superhero from central casting. He is not, however, an outlaw vigilante. He is

an FBI agent, albeit one who was appointed via some special provision reserved for

people who can throw a bus. Unlike many heroes, he’s hardly a lone wolf.

Instead he’s an order taker, a team player and a bit of a mooch. He borrows

equipment from other heroes. Shield calls in other characters from Pep Comics

to help him out. Stories started in the Shield’s lead 12 pages are concluded in

back up features, either because he got stumped or needed assistance. He’s a

good follower, a non alpha male. He’s easy going and easy to identify with. And

he’s the only red headed superhero. All in all, a rather distinct character.

The second feature is the Comet. Although Comet and Shield have comically identical origin

stories, the similarity ends there. Comet is the product of Jack Cole, one of

the few masters of the comic book form. Cole is a great illustrator with a wild

wit. My thinking is that the Comet was picked up by MLJ after it had been

rejected elsewhere. Designed as a back up feature, there’s only six pages of it

per installment. It is a concentrated blast of over the top violent mayhem.

Unlike the Shield, Comet is a murderous flying vigilante. He has the ability to

indiscriminately vaporize anything he looks at. The general set up of the strip

is that the bad guys commit one unspeakable atrocity after another until the

Comet either tracks them down or blunders into them. Then the Comet swoops in

and dissolvo-vision blast murders the crooks. End of story. Comet does have a

spectacular uniform, which only Jack Cole seems to know how to render. Once the

Jack Cole material is used up, the long term dramatic issues with the plot

construction become apparent. Although the feature isn’t very long lasting, it

sets a tone for the entire MLJ line.

SGT Boyle is the

third feature. Boyle is an unmarked superhero, a soldier performing improbable

acts of daring. The strip uses the excuse of Boyle being a soldier to justify a

high body count. It seems to have been popular since the feature also appeared

in Jackpot Comics. A similar character, Corporal Collins, headlined in early

issues of Blue Ribbon.

Queen of Diamonds

(or Rocket and the Queen of Diamonds) rips off both Buck Rogers and Flash

Gordon at the same time and does both in the most pedestrian manner possible. Although

started in the 4th slot, it will move further back in the pages of

Pep as time goes on.

Fu Chang. Imagine

Charlie Chan as a superhero. Through his devotion to ancient Chinese

deities Fu Chang has been gifted with a

variety of powerful figurines, called chess pieces. When deployed, each figure

grows to man-size and performs a specific function at Fu Chang’s command. The

concept is both interesting and well executed, although its ill-informed view

of Chinese society cleaves closely to the Charlie Chan movies. Fu Chang

maintains it position in the middle of Pep throughout the first year.

Bently of Scotland

Yard. Modernized Sherlock Holmes grafted onto the hard-boiled idiom. Other

than the setting, a straight up detective strip. Slips positions in the book,

but stays on for the first year.

Press Guardian

(also known as The Falcon) is another superhero feature. Falcon is a reporter

who comes to the defense of other reporters. He makes it his mission to go

after any entity—private, government, foreign or domestic—attempting to impede

the freedom of the press. It’s a visually well-designed character and the focus

on a single cause makes Falcon unique.

Falcon never appears in any other comic, but he does move up several

positions in Pep Comics during its run. As with Comet, my thinking is that this

feature was picked up by MLJ after having been rejected elsewhere. The

character is redesigned early on (simplified to make it easier for a less

talented person to draw), probably because the original material had run out.

Midshipman. Between SGT Boyle and Corporal Collins MLJ

had the Army and the Marines covered as far as super beings in uniform were

concerned. Midshipman carries that theme to the Navy. Oddly, the sailor is the

most straight-laced of the over-the-top lot of them. War is in the air and MLJ

now has all of the services covered. Until real war breaks out, most of the

action is against fictional Asians and Europeans.

Kayo Ward is an

imitation of the popular Joe Palooka comic strip, done straight without any of

the humor or charm of the original.

Add a rotating crop of single page funny animal gag strips,

a stray promotional page and a two page text feature and this is what makes up

Pep Comics for the first year or so.

The first issue of Pep Comics was followed by the first

issue of Zip Comics the next month. If anything, Zip is more of an economy move

than even Pep was. While it takes three months to publish a comic book, it

takes two to three months to determine how well they are doing. Five months

into the venture MLJ is getting their

first returns on Top Notch, which triggers changes being made to that title.

Month six brings bad news on Blue Ribbon. Pep must have been a pleasant

surprise, although probably a head scratcher. I’m not sure how well Zip did,

but its contents started shifting as soon as issue five.

Pep Comics is promoted to the next level of circulation,

probably occupying its own print run. If

MLJ is similar to other comic companies, this leaves them with a choice: Cancel

one or two titles or launch another so that they can continue printing

economically. Because they are veteran pulpsters however, MLJ decides to pull

the ploy of skipping months, effectively stretching the sales times for their

slower moving titles. To keep up their seeming distribution requirement of two

titles every two weeks, MLJ begins issuing quarterlies and special editions.

Since all MLJ can count on is Pep Comics, they effectively

clone it. The first of the clone attempts is Shield-Wizard, which adds more to

Irv Novick’s art workload. (Novick will also be the lead artist for Zip Comic’s

Steel Sterling.) MLJ is operating under the reasonable assumption that the

Shield is Pep’s big draw. Pairing Shield with Wizard continues a trend started

in Top Notch, but it’s a dubious match, which MLJ corrects early on by

effectively writing the Wizard out of the magazine. Instead of being about the

Wizard or team ups with the Shield, back pages are used to recount the

adventures of the Wizard’s ancestors.

This is a nice picture of a pirate. And Black Swan sounds

like the name of a pirate ship. But beware ye hardy land lubbers who buy this

comic book, there isn’t a pirate in its pages. Instead, the prospective pirate

aficionado will find the typical contents of Pep Comics. (This is a later

issue, but MLJ is notorious for such thrown together nonsense.)

On the other hand, they may not have been altogether sold

that the Shield was Pep’s draw, since their next quarterly, Jackpot Comics, featured

all of Pep’s main back up features grafted onto the leads from Top Notch, Blue

Ribbon and Zip. Or they could have been

salvaging art from magazines which were destined for reconfiguration. MLJ never

bought a piece of art they didn’t use.

After a year the prospects for the MLJ project seem poor.

Having one wildly successful comic book was fine for Hillman and Fiction House,

but those firms had other things going.

MLJ has Pep and turds. The M in MLJ soon cashes out. L is sticking with

it, but hedging his bets and heading back into pulp magazines. J will spend his

time reconfiguring the MLJ line.

During the first retooling of Top Notch, a new character called

the Black Hood was introduced. Black Hood is later repurposed for a character

pulp magazine. To my knowledge this is the only character to have ever

undergone the transition from comics to pulp. It lasts two issues and

constitutes the first offering from Columbia Publications. As Columbia/Close-Up/Balatine

Publications this firm will remain a producer of pulps, digests, sleazy

magazines and paperbacks through the mid 1960s.

There is a distinction between MLJ and Columbia, but it is

slight. Columbia is the last of the big pulp houses to start up and the last

one in operation. At the time Columbia started, however, it wasn’t the best time

to jump into pulps again.

With smudgy printing and bad art, MLJ didn’t have too many

good directions to go in. They were making cost free efforts at distinguishing

themselves. They double down on superheroes and the sort of unhinged violence

and bloodletting that was modeled in the Comet feature. And they are not afraid

of adding an occult angle to it.

This was also the tactic that the Double Action and Red

Circle pulp lines had taken with their non smut magazines. Although there is no

corporate connection between the Double Action and Red Circle pulp lines and

MLJ and Columbia, IT’S THE SAME PEOPLE. Torture porn is their thing. And MLJ

isn’t the only comic house cranking this crud out for kiddies. A for profit art

commune (Lev Gleason Publications) culled from MLJ’s primary art vendor is the

leader in the sadism for tykes field. All of this made MLJ well situated to

follow this trend.

Black Hood is MLJ’s torture porn king. His origin is torture

porn. (Especially the pulp version.)

He’s adventures are outings replete with stabbings and beheadings and

mass murder. The character has some traction and is soon in all of the MLJ

comics except Pep. One source indicates that there was a movie deal for the

character on the table at one point.

Here’s a fine children’s comic book. Unless my senses are deceiving

me, it appears this hooded black man is about to behead a curiously posed white

woman. At the behest of a witch.

This one could only be worse if it was rendered better. From

what I can tell, a tribe of mostly naked, half-decapitated black men are

attempting to guillotine this woman. Note the brunette’s party dress and doggy

posture. I know I am starting to sound

like Dr. Wertham here.

Eventually the bloodletting inflicting the rest of MLJ’s

comics circles its way back to Pep Comics. So far, they haven’t touched the

Shield in nearly a year, other than to give him a sidekick. (More about him

later.) Having realized the limitations of Comet’s formula, MLJ retires the

character in a most spectacular way. The Comet is machinegunned to death. His

grieving brother (who has never been mentioned previously) decides to avenge

him, abandoning his job and taking up costumed crime fighting as the Hangman. That’s

just what the world needed, a superhero with a lynching gimmick. MLJ is so

confident of this character that he is sharing cover space with the Shield for

several issues.

He’s not as big of a scene stealer as Shield’s sidekick,

Dusty, however. Dusty is a red headed tween introduced to aid the Shield, ala

Robin, in the 11th issue of Pep. Dusty (the Boy Detective) starts

swallowing space, appearing as his own feature and as part of a team-up feature

with the Wizard’s sidekick Roy (the Super Boy). He and Roy are also the

Hangman’s sidekicks. They appear in their own feature in the new Hangman Comics

and are soon also hoovering up the Wizard’s space in Shield Wizard. In short

order, the non-super carrot top had twice the comics real estate as his mentor.

It would be the start of a trend at MLJ.

Life didn’t get any easier for the Shield. As part of the

tweaking process, he lost his powers. This set up a Marvel-type existential

crisis as the Shield flails between attempting to regain his abilities and

efforts to simply carry on in his chosen trade without them.

As momentous of a change as this may seem to the Shield, a

more important change to the Pep roster of features had occurred a few issues

earlier. The J in MLJ (John Goldwater) and his aid Harry Shorten are throwing

spaghetti at walls type changes throughout the line. MLJ is on the losing end

of a bidding war for the services of their art shop. Their competitor, Lev

Gleason, is a flat out socialist, offering his creatives up to 80% of the

profits at certain circulation levels.

In an effort to pay the artists more for their work without paying more

for art, MLJ attempted to bypass the studios, offering opportunities for

freelance work. (If your art vendor gets word of that, you will be cut off.) It

wasn’t entirely a successful effort, but it did make them an open transom shop.

There is a certain breed of artist who doesn’t want to work

for a studio. And the studios were as follow the leader bound as the publishers

were. MLJ took a lot of chances on material and people. With mixed results.

Sometimes MLJ was handed a good idea and then screwed up the

execution. Case in point is the wonderfully designed Web character. They

couldn’t even keep his hair color straight.

Irwin Hassan penned two beautifully rendered installments of

the Fox, only to have the printer screw it up in coloring. No one at MLJ or

their printer had the sense to know that you cannot make a character jet black.

It becomes a smudge. That is the reason that Batman is blue and grey. Black

needs to be implied in four color comics. Black the color is only for outlines.

Below are two examples of errors the printer should have caught.

Note the Royal Purple title box over black lettering and the

angular blotch at the right center of the composition. Not much is going to

help this Lin Streeter illustration,

but the errant darkness behind the skeleton dude is a distraction. It is my

opinion that this scene takes place in a log cabin, somewhere where the laws of

light have taken leave of their senses. It is also my opinion that the words

‘TRUE LIFE’ are supposed red as opposed to the words ‘SENSATIONAL TRUE’. A

printer who lets this out of his shop does not care. Or perhaps the printer was

as confused as I am as to what is being advertised in the first place. Are

‘Sensational True Life Adventures’ a new feature of Blue Ribbon or are they

descriptive of poor old Captain Flag?

I am going to side with ‘does not care.’ What are the words

running through the Hangman’s legs? Which genius decided to cast the sky the same

color as the Hangman’s cape, thus obscuring the only redeeming portion of this

travesty. Beyond the errors, what we see here is evidence of Irv Novick being

worked to death. I have spent several thousand words on the premise that Pep

Comics was MLJ’s show piece, only to have it shot in the legs here.

Except for the piss poor printing, which was a constant in

the pre-war era, MLJ comics were wildly uneven. The Pep Comics package seems to

be where they put their more thought out material. By the second year, some

features which had originated in Zip or Blue Ribbon or Top Notch were finding

showcases in Pep. In the 22nd issue of Pep, MLJ introduced a new

feature called Archie.

There is a history of MLJ Comics currently out which I have

not read as yet. The Archie Comics corporate line is that Archie was a group

think creation. Prior to Archie showing up, Pep introduced Dusty and seemed to

be heading in a kids as heroes direction. They also touted Captain Commando and

his Boy Soldiers in previous issues of Pep. Lev Gleason, with whom they shared

an art vendor, originated the boy hero trend, with Crime Buster appearing in

Boy Comics and eventually the Little Wise Guys in Daredevil. Beyond comics, the

teen themed Andy Hardy series starring Mickey Rooney had been popular with

movie audiences of the time. The teen audience, called bobbysocksers, were

being recognized in many mediums. An argument can certainly be made that

something Archie-like was in the winds.

I don’t buy it.

During Archie’s first flush of success, MLJ was more than happy to tout Archie

as sole creation of Bob Montana. The

characters are caricatures of people Montana went to high school with. He had

been pitching a similar strip to other publishers. Other than not screwing it

up, MLJ’s contribution to Montana’s work is hard to pin down.

If MLJ was transitioning away from its badly drawn Action

Thrills Adventure genre, it was into badly drawn funny animals. There is

nothing like Archie in any other comic book or comic strip. There are no other

funny humans in any other MLJ magazine.

Archie is a unique feature. Unlike the power depleted Shield

or the hair color challenged Web or the fluctuating Wizard, the strip shows up

fully realized. It does evolve a bit, but all of the elements are there from

the start. Moreover, just as comic book art, Archie is better executed than

anything else MLJ regularly published. Archie is polished. It’s obviously good

stuff. That’s why they slate it for both Pep Comics and its ancillary Jackpot

Comics. Oddly, they only cover promote the feature in Jackpot Comics.

Other than knowing Archie was quality material, I am not

sure if MLJ knew what they had. MLJ was editorially unhinged enough to allow

just about anything, but they may have been leery about the Archie feature’s

recurrent themes.

Allusions to the Andy Hardy series seem to miss the point.

Andy Hardy is turn of the century nostalgia in contemporary dress. Hardy is the

son of a respected politician, the baby of three siblings. Archie is the son of

a frazzled, overweight, workaholic middling businessman. Initially Andy Hardy

is an inhabitant of a family setting, a minor character in a drama involving

his older sisters. Archie is probably an ‘oops child’, the single offspring of

older parents. Andy Hardy’s parents hover over him. Hardy’s plotline turning

points amount to fatherly talks setting the boy straight, firmly but kindly. By

contrast, Archie’s parents seem to be sick of him. They limit their

interactions with Archie to feeding the kid and screaming at him. Andy Hardy is

a pathological liar who lives in a universe where his powerful judge father can

bail him out of anything. Archie is a free range child of the Depression, well

aware that he needs to get himself out of any problems he might get into. As

personalities go, Archie has more in common with the character portrayed by

Jack Benny than he does Andy Hardy.

There is some cross pollination between Archie and Andy Hardy as time

goes on, but how much of this is intentional is impossible to say. (And it is

hard to sort who is influencing whom.) The Andy Hardy movies became a star

vehicle for the prat falling talents of Mickey Rooney. Similarly, the Archie

feature was purposed for sight gags, filling in the stray spaces where MLJ’s

funny animal pages had once been. Thematically, Archie and Andy Hardy are polar

opposites.

Archie is about sexual politics and the arbitrary nature of

power. Archie is an interloper in a late middle-age marriage, another mouth to

feed--of whom little is expected except that he might some day fend for

himself. He doesn’t get Andy Hardy’s allowance. Archie gets a job. Andy Hardy

is gifted a car. Archie has to build a car, piece by piece, from parts he buys

at the junk yard. (Archie’s dad was game enough to let him try and then did not

complain about the results.) Andy Hardy’s life was laid out for him. He will

some day go to college and meet a nice girl and then become something

professional. Archie’s goals are more immediate, his days spent navigating

between bleating authority figures. Everyone in Archie’s life values him solely

for what they can get from him. And this may be the way his life will always

be. Archie lacks the resources, aspiration and vision to change his

environment. Instead, he goofs on it—not to the degree that his sidekick the

proto-beatnik Jughead does, but to an unhealthy degree nonetheless.

Complicating matters further, Archie has ceased having thoughts above the

waistline. He isn’t fighting it. He isn’t confused about it. This is one of the

reasons that most of the girls in Archie look alike. He’s not here for your

hair color or your cookies. To Archie, all girls are the same. This is a bleak

set up for a comic strip, however it is similar in construction to Popeye. In Archie’s case, it is more derivative of

Marx Brother’s movies, wherein the less redeeming the character’s motives are,

the greater the capacity for comedy. Montana himself is the child of Vaudeville

performers. He knows all of the bits and all of the formulas and works them in.

It’s a nice package, adaptable to long or short forms.

After all of the shifting around is done, Pep Comics takes

off like a rocket. And that’s it. Zip and the rest are flatlining. MLJ might

have attributed some of Pep’s success to Archie, but he was hardly saving

Jackpot Comics. (Jackpot may have had too much of the other features.) Hangman

Comics has failed and is retitled in favor of the Black Hood. Black Hood has

also displaced the Wizard in Top Notch. I imagine the returns on the Black Hood

titles were acceptable, but the rest of the line is headed to zero.

MLJ does figure it out. Ten issues after his first

appearance, Archie merits a cover mention on Pep Comics. Shortly after this, the first issue of Archie

Comics is put out as a quarterly. In form, it is a funny animal comic with

Archie in the lead spot. It will be a full two years before the frequency of

Archie Comics is increased and several more years before the Archie content of

Archie Comics is increased.

Which is to say that MLJ only sort of gets it. Deciding that

funny people are the trend, MLJ begins spreading that throughout its line,

uncomfortably having their superheroes shunt cover space for untried comic book

comedians. At about the same time, the back up features of these magazines are

being swarmed by a menagerie of funny animals. This revamp of the other titles

seems to have failed.

It is more the rule than the exception in entertainment to

not know why something is a success. The publishers of Action Comics took

several months to determine that Superman was their most attractive feature.

MLJ is clearly attempting to diagnose the appeal. They increase Archie’s page

count in Pep and give the feature its lead position. Other than that, they

don’t want to mess with it. As long as Archie is in Pep Comics, its sales are

climbing. It’s the rest of the line they need to bulk up.

Archie is not as scalable as one might think. Efforts to

knock Archie off have largely not worked. There is something about Archie that

is specifically working. Getting more Archie is taking a chance at over working

Bob Montana or giving him considerable help. And giving him help is no

guarantee that the concept can be replicated. This is the reason the publishers

seldom touched a creative team on hit features. (On the other hand, Walt Disney

did it all the time.)

Hollywood then descends on MLJ Comics. Both Archie and the

Black Hood are picked up for radio treatments. Republic Pictures has optioned

the Black Hood for a movie serial. Suddenly life is good. They hire a new

printer.

MLJ is not giving these properties away. There is

considerable money involved. Moreover, it is free advertising for the comic

book. It would seem as if the firm’s near term future is assured. Unfortunately

the Black Hood series fails in under a season and the movie serial is not

finished. Archie, on the other hand, becomes a hit show and stays on the radio

uninterrupted for ten years.

It is not long after the Archie radio show rates as a hit

that MLJ begins to roll out tests to see how much Archie they can pump out. By

the “one risk” terms of the comic book industry, MLJ owns Archie the character.

Early on, keeping Bob Montana happy seems to be a corporate goal. Montana never

has the artistic control that Batman’s creator did, but he did get a bump in

pay. And MLJ was happy to promote him as the man behind the Archie story. They

held Montana’s job for him when he was drafted. In 1947 a newspaper comic strip

syndication deal came through, which Montana illustrated for 35 years. Things

fell apart later on.

Pep Comics underwent a very quick transformation as a result

of Archie’s emerging success. They stayed with the anthology format, but

steadily dropped most of the superheroes. Hangman was the first casualty. Then

the Shield’s cover mentions started to get more and more oblique.

It might have made more sense to simply rename Pep Comics,

but they renamed the company instead. Without any exclusivity to the Archie

feature, Pep faded back into the pack. Slowly but surely new titles featuring

the Archie cast started cropping up. In its last phases, Pep was actually the

worst selling of the Archie line. The connection of the title to the character

or to anything whatsoever had been forgotten. As for the Shield, he wrote the

audience a letter and vanished. His invulnerability, super speed and amazing

strength now permanently gone and without hope of return, Shield resigned his

position in the FBI and enlisted in the army. Better that than fishing with

Veronica.

**

WE DON’T KNOW EVERYTHING! Your comments and corrections are

actively encouraged.

PS: I love MLJ Comics, mostly because they are so wild and

wildly defective. I will save my publisher’s bio of Columbia Publications for

another time. Archie had another few

spates of innovation, post the 1950s which I intend to cover. But I am going to

read the new MLJ History first.

No comments:

Post a Comment