City of the Living Dead: An examination of Dystopia in

American comic books.

In our last posting on Dystopia, it was stated that global fictional

un-utopia came in two flavors: Literary Dystopia, which is an exercise in a big

bad idea playing out on an individual (1984, Brave New World) and Pulp

Dystopia, wherein whatever it is that went wrong is treated more or less as

scenery (Mad Max, Hunger Games). While Literary

Dystopia adheres to the plot conventions of Horror, Pulp Dystopia cleaves to

tropes found in the Western, Romance or Fantasy genres. That Pulp Dystopia has such flexibility is one

of the reasons for its current popularity.

My own contention is that there is an attractive democracy to Pulp

Dystopia, a world devoid of celebrities and distinctions in class. I believe

that Pulp Dystopia and Fantasy are occupying the same popular space that Westerns

once did.

Attempts to tie this new Pulp Dystopia back to the actual Pulp

Magazine era are dubious. The pulp

magazine form had faded by the time 1984 first hit the literary world. The

other powerhouses of the dystopian form also came to us from the world of lit

fiction. Our pals in the Sweats (linear descendants of pulp magazines, slick

paper photo offset periodicals plying pulp genres) were still rolling off White

Slavery and Nymphomaniac World War II tales at the time Brave New World and Fahrenheit

451 were setting the pace in hardbound form. Real contributions to Dystopia

were made in paperback, such as A Clockwork Orange, but there is next to no

connection between this and the world of pulp in terms of authors, editors or

publishers. (1)

When it comes to popularizing Pulp Dystopia, I am laying the

blame squarely at the feet of movies (Mad Max, Logan’s Run, Blade Runner,

Japanese Animation), role-playing games (Gama World, Shadowrun, Morrow Project)

and video games. That said, I may have

cut the other spawn of the pulps, comic books, somewhat short as far as

covering their contribution.

Comic Books have been parading dystopian themes since their

inception. While researching another project I ran into a slew of titles with a

dystopian bent. As a whole, the comic

book presentation of dystopia peaked in the early 1950s, which indicates that it

is breathing the same air as Literary Dystopia. Both the comic book version of

dystopia and Literary Dystopia emerge at the same time and seem to have the

same historical influences. While not

exactly conforming to the later idiom of Pulp Dystopia, the Dystopia found in

comic books is very distinct from the co-emerging Literary version.

In our last posting on dystopia, we traced the earliest

emergence of Pulp Dystopia to a cycle of novels appearing in the character pulp

Operator Number Five. This series, known

as The Purple Invasion, was a late 1930s imagining of the WWII to come, albeit involving

a fictional nation invading the United States.

Much of the early comic book dystopia follows something along the same

lines. Nearly every escapist action character took his or her turn at ending

the paraphrased coming war. Comic book

anthologies were replete with eight to ten-page Armageddons wherein a singular

figure is instrumental in the defeat of some Asian or European dictator. Even

Superman took a turn at this, in fact several. That certainly is a form of Pulp

Dystopia. As opposed to going through the horror process of learned

helplessness, the superhero attempts to solve the crisis. But this may be

defining dystopia too broadly.

There were several superheroes who fit the Literary Dystopia

mold of being trapped inside a pervading big bad idea, mostly set in the

future. All-American Comics featured Gary Concord, the Ultraman, the superhero policeman

of a world-wide government. Power Nelson

was situated similarly, the sole superhero cop in a future world plagued with

fantastic disruptions to civil order. Both Power Nelson and the interstellar dystopian

Spacehawk wound up plopped down in 1940s America once real-world WWII became

eminent. (Sorry about your future setting, the publisher needs you here now.)

Super American took this concept one stage further. He lived in a future where

everyone was a superman. Having lost some sort of draft lottery, he was sent

back through time to aid the WWII Allied cause. Once the real war was under

way, a lot of the paraphrasing and dystopian themes went by the wayside. One can argue whether WWII constitutes a dystopia

itself (two racist totalitarian nations attempt to enslave the world), but the

stories which play out do not follow either Literary or Pulp Dystopian

formulas. (2)

Literary Dystopia does not pick up steam until after WWII

and is largely inspired by the aftermath of that conflict. Mechanization had advanced to the point wherein

an unprecedented amount of control over the populace could be exerted by authorities.

Technology was now such that we could

blow ourselves out of existence. With

the fascist, racist, totalitarian empires defeated, half of the world had been

enveloped by atheist, collectivist, totalitarian regimes. That’s a lot of angst.

Literary Dystopians broke the mold for popular novels. Not much action. Characters are uniformly

Alice in Wonderland types. Backstory is ladled on. And then it plays out like a

horror story. Breathing the same air, in 1947 comic/pulp publisher Fawcett

released its own dystopian work.

Or at least it looks the part. At first glance, Anarcho

Dictator of Death seems to be some sort of arty expansion of the comics form, a

“Complete Novel in Comic Strip Form.” Fawcett was one of the Golden Age of

Comics Big Three sales leaders, a true innovator and top-quality operator. The Saint

Paul-based firm was highly connected and very politically active. (3) Even

before WWII had ended, Fawcett was sounding the alarm about communists through

its spokeshero Captain Marvel. The firm seldom missed an opportunity to defend

the free enterprise system or decry evidence of creeping socialism.

Taken in the best possible light, Anarcho Dictator of Death

is a warning that the peace we have won requires defenders, that the peace is

precarious and that there is a need to be vigilant against lingering forces of

global division. But that is cutting

this work way too much credit.

This is an unmarked superhero comic. Had Fawcett been interested in sending out a

serious warning as to the return of fascism, they would not have waited three

years after the war in Europe’s conclusion and might have used a higher profile

hero--Captain Marvel, or more appropriately, Spy Smasher. (4) Instead Comics

Novel features Radar, a back page non-entity which had been running as the last

slot feature in Master Comics since 1943.

In my opinion Radar isn’t on the cover because he has no

sales draw. The Radar feature does have

an interesting backstory. This superhero

was commissioned at the request of the US Government, its purpose to promote a

Wendell Wilkie global good guy government version of the United Nations,

complete with its own anti disrupting the new world order police force. (5) Radar’s

origin was featured in the 35th issue of Fawcett’s top selling Captain

Marvel Adventures title and includes a key role for their flagship hero Captain

Marvel. In this origin it is revealed

that Radar comes by his abilities naturally, being the son of a circus

strongman and a Gypsy fortune teller. (Several

sources have stated that Radar is a non-powered hero like Batman. This in not

the case. Radar has that level of super strength which allows him to shoulder

open an iron door but not quite snap out of a pair of handcuffs. He can read

minds and has a remote viewing ability which accounts for his nickname.) At the

end of his origin, Radar is requested to blaze the trail for an unofficial

International Police Agency, acting as a global Jedi Knight answering only to

FDR, Winston Churchill, Joe Stalin and Chiang Kai-shek. In the last panel it is

announced that Radar is heading off to Master Comics to share anthology space

with Captain Marvel Junior and Bulletman.

My best guess is that Anarcho Dictator of Death is an unused

Radar serial, probably commissioned in 1945 for Master Comics. Radar appeared in several continued stories early

in its run. Something went wrong with

this story line between the time it was sent for art and the time it was

completed. The first obvious issue deals with the people Radar supposedly

answers to: FDR is dead; Churchill has been voted out of office; Chiang Kai-shek is being chased out of China; and Uncle Joe Stalin is no longer in the good guy

club. By that time it was also becoming obvious that the United Nations was

going to fall far short of its idealistic designs. Although Radar was still appearing in Master Comics

at the time that Anarcho Dictator of Death was released, he had undergone the

fate of all comic book counter-spies and aviators—he was fighting aliens from

outer space.

Radar would disappear from Master Comics shortly after

Anarcho’s release, replaced by Hop-a-long Cassidy. In Anarcho Dictator of Death, Radar’s

International Police Force is an operational entity, with offices and prisons

all over the world. His sidekick is a

Kai-shek issued fellow international cop named Chen. They are engaged in rounding up fascist sympathizers

at the onset of the novel. The tone is never dystopian, nor elevated above that

of standard comic book fare, and any attempt at reading this for additional

meaning will be dispelled midway through the first chapter. Far from channeling

George Orwell, writer Otto Binder is doing a bad imitation of movie serial

screen scribe George Plympton. The story is more about hidden doors than it is

about politics.

Are there any Dystopian elements? There is a torture scene…

But Radar, being a superhero, shrugs it off and judo flips

Anarcho into a troth of lye built into a hotel room’s floor. (Don’t ask.) As opposed to sending political warnings,

Anarcho is about salvaging 48 pages of expensive comic art. They slid Anarcho into the slot of some cancelled

comic title, stuck a two tone ‘arty’ cover on the thing—and issued it as a

single title, without advertising, in order not to impact their circulation

figures.

Anarcho is something of a rarity. There were some free-standing

anti-fascist propaganda works in comic form, such as It Could Happen Here. Literary

Dystopia only appears in earnest somewhat after Anarcho’s issuing. Other than

occasionally sideswiping its feel, dystopia was largely ignored in the comics. Even the popular Horror/Mystery anthologies avoided

dystopian themes, favoring more visual supernatural stories involving witches and

zombies.

On occasion, dystopia was simply grafted onto other genres.

The idea of atom bomb secrets being stolen by America’s

enemies is absolutely terrifying. Atomic

weapons spreading into the hands of unscrupulous parties is the thing of nightmares.

That one’s fellow citizens—your neighbors—might be so low as to give aid to the

process of disseminating world ending weapons to foreign powers is enough to

evoke paranoia. Sadly, all of the above

happened and is still happening today. But it happened first in this 1950 Avon

comic book.

Atom bombs were supposed to make war obsolete. The Korean conflict proved that this wasn’t

the case. Our pals in the war comics business weren’t quite sure what to do.

Some of these are disguised anthologies about the Korean

conflict, dressed up in atomic bunting for additional sensationalistic sales

appeal.

Comic books in the early 1950s are shameless.

All of these are series books. Atom Age Combat was published

in two series, one in the early 1950s and one in the middle 1950s.

Although most of these war anthologies are fairly pedestrian

1950s era stuff, there are many examples of Armageddon and Post-Armageddon

tales in their pages.

The trend largely petered out by 1957. At that point most of

the war comics publishers went back to depicting WWII--which is where they

stayed until the demise of the war genre in comics.

The bulwark genres of comics in the 1950s were Horror/Mystery,

Romance and True Crime. (6) This is a reversion to the mean, since these were

the same genres which propped up the remaining pulps. Although Dystopia was an

extension of the Horror/Mystery genre—a horror story writ very large—there was

all of one horror comics anthology which routinely ran it.

This is a minor title from a minor publisher and only a

minority of the stories fit even the Pulp Dystopian mold. As with most horror,

it’s mostly monster stories.

Big Brother, Energy Shortages, Environmental Collapse and

the other boogey men of Literary Dystopia are hard to do in eight-page comic

book chunks. That said, comics did like to ape the globally oppressive feel of

Literary Dystopia. Lacking time for a backstory, comic books substitute

something visual as an analogy. It’s a

big bad thing and it’s in the midst of winning.

Our hero has given up on the idea of defeating the thing or saving other

people and is instead simply focused on surviving it. Or the hero is fighting a

seemingly hopeless rear-guard action. It clings somewhat close to the conventions

of Literary Dystopia, only with a physical monster taking Big Brother’s place.

This may be the first zombie graphic novel. Zombies were popular in all mediums in the late

1940s and early 1950s. Most comic book

publishers of the time were only willing to produce comic books in series

form. This publisher, Avon, sells comic

books by the issue. If they have a strong

story idea, they will make a title for it, even if it’s only a one-time thing.

(7)

Aliens also make good Big Brother stand-ins. There was a

flurry of UFO sightings in the late 1940s which led to something of a pulp

fiction craze. This particular graphic

novel (they were called comic books at the time) was written by Walter B.

Gibson, the primary pulp writer of The Shadow.

Dystopian themed anthologies do start to appear in 1950s

comics, but they are all weird genre grafts. Comic book Dystopia falls into the

broad general category of “Space and the Future Suck, Too.” If we include oddball works such as St John’s

Tor we could add “Prehistory Was No Fun, Either” or the raft of still strong

selling jungle books, “The Wilderness Also Sucks.” The underlying message is that there is no

geographic escape to conflict, that no matter where you go oppressive existential

threats will greet you. That may not be

a form of dystopia, but it is hardly the warm and fuzzies of Star Trek.

Most of these are from Charlton Comics, a firm known for its nimble

capacity to triangulate trends.

Of these, the most successful title is Space War—a dismal,

violent vision of the future.

Some of these anthologies did feature continuing characters,

inhabitants of offshoot dystopian realms unrelated to the other stories. There

were also a few dystopian character titles, all in the Space and the Future

Sucks, Too category.

Major Inapak is pitted against an evil global Earth

government, leading a rebellion in the remote space colonies.

Captain Science lives on a future Earth which is being

invaded daily by a coalition of alien space nations.

Space Busters: Alien invasions have become so pernicious that a global Earth

government has decided to go after them like an organized crime task force.

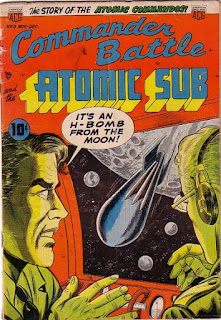

Commander Battle and his Atomic Sub find numerous uses for end

of the world weapons. Although the

premise is as close to Literary Dystopian as it gets, most plots are typical Bug

Eyed Monster hunts. It seems to have

been the inspiration for a later Irwin Allen television show.

My initial intention was to chronical these titles and

extrapolate their possible influence on the development of Pulp Dystopia. Not

all of my ideas are any good. As any student

of evolution will tell you, some paths just dead end.

While comic books acknowledged Literary Dystopia, their

approach is strictly cosmetic. Key to the early dystopian form are disasters propelled

by human bureaucracy. Like mental powers, bureaucracy isn’t a particularly

visual thing. If you substitute vampires or aliens or zombies for Big Brother,

you’re not dealing with dystopia but rather a more pedestrian aspect of science

fantasy. Pulp Dystopia focuses more on the

effects than the causes of a crisis, and was never chanced on as a repeated

literary construction in comic books.

The current Pulp Dystopia TV hit Walking Dead did start as a

comic book, but it doesn’t have much in the way of precedent within the comic

book form. Even as a comic book, it has more to do with copping the feel of

George Romero movies than advancing any idea from the world of four color sequential

art.

This is not to say that Walking Dead is the only modern era

comic book to have played with Literary Dystopia or Pulp Dystopia. The Kamandi and Kilraven (War of the Worlds)

series put the post global disaster themes front and center. (8) Underground Comix anthologies such as Class

War, Slow Death and Zap ran stories set in a decadent version of after the fall

of now. True to Pulp Dystopian form, many were more interested in exploiting

the shock value of leather clad women walking their sex slaves like dogs than

explaining exactly what circumstances may have led to this. Mainstream comic

book publisher Charlton had at least two continuing titles set after doomsday.

Comic books have generally had little truck with dystopia in

any of its forms and have lacked the influence to impact the new Pulp Dystopian

form. That the medium has dodged having

an influence for 60 plus years does not mean that it will continue to do

so. As long as Pulp Dystopia remains an ascendant

genre, the chances of it making a strong showing in the graphic novel form

remain high. It is a mainstay of the

Japanese version.

WE DON’T KNOW EVERYTHING!

Your comments, corrections and

criticisms are always actively invited.

Due to the prevalence of spam, we have

taken to monitoring our comments section.

Your comments may not appear immediately.

(1) There

was a non pulp separation in Science Fiction, led by the digest title Magazine

of Science Fiction and Fantasy. In this new school, science fiction was getting

away from the camoflague Western Space

Opera, bug eyed monster hunting, action plotting emphasis found in the pulps

and more towards relativism and relevancy.

Ray Bradbury, though a pulp era author, was a part of this trend and his

Literary Dystopian work Fahrenheit 451 is one of the better examples.

(2) Most

comic book superhero stories are set in what I have dubbed the Modern Thrills

genre. It’s the real world but… your

wife is a witch… there are secret societies of vampires lurking about… there

are occasional super powered beings.

Everything else is normal and the supernatural elements that do exist do

not have the sway to make overall changes in society. Instead, the normal world

sort of seals up wounds made by the fantastic hermetically, showing no lingering

signs that anything out of the ordinary has transpired.

(3) Fawcett

was well situated to withstand the sort of criticism that would later engulf

other comic book publishers. Not that

they were any less vulgar. Just in

Anarcho they run an extensive torture scene and portray the people of Tibet as

being demon worshippers. As opposed to policing their content, the firm had

hired the First Lady and the daughter of Freud (along with Admiral Byrd and a

bevy of other luminaries) to sit on their editorial board. These people were

surely not reading the 60 comics per month Fawcett produces. It’s pure bribery.

The names of these prominent establishment Americans on their comic book

mastheads provided a very nice political smokescreen.

(4) Spy

Smasher was Fawcett’s big hitter in the comic book spy game. He had been featured in an early WWII movie

serial and appeared in several of the firm’s comic titles. It’s a big seller, drawing better than their

licensed Captain Midnight title. Come the end of the war, however, both the

Ovaltine owned Captain Midnight and Fawcett’s own Spy Smasher are in

existential trouble. With no war raging,

neither of these guys has a reason for being. Fawcett took the typical tact of

sending Captain Midnight into outer space.

Spy Smasher, at about the same time as Anarcho’s release, was

re-christened Crime Smasher and then did a fast fade from view. Like Anarcho, Crime

Smasher was given a one shot title and was never heard from again.

(5) The

US Government does seem to have a Department of Messing With Cartoon

Characters. Weird as it seems, this is

not the first record we have of the government making such a request. The popular Don Winslow of the Navy character

was also commissioned by the government, supposedly to aid in recruitment.

Winslow’s adventures in comics, radio and the silver screen were just as

fantastic as anything Captain Marvel participated in. At this point Winslow was

also appearing in Fawcett comics.

(6) This

was only the case of publishers who had failed to find a niche to

monopolize. Post the collapse of Fawcett,

Superman’s publisher DC Comics had a

monopoly on the diminished superhero genre.

Archie had a monopoly on teen humor.

Dell Comics had a monopoly on licensed animation characters. Post the emergence of the Comics Code, the

True Crime genre would vanish. EC wound up with Mad Magazine, to this day the

best selling comic book in America. Harvey would chance on a theme of

dysfunctional weird kiddies (Casper, Richie Rich). Everyone else scrambled.

(7) In

general, distributors of the time wanted a commitment from the comics

publishers. A publisher had to provide X number of new titles a week, mostly

for distribution to local pharmacies. Avon was unusual, being effectively

distributor sponsored. It was piggybacking its comics off of a system geared to

circulating paperback novels.

(8) Kamandi

was a very imaginative Jack Kirby work, however it’s standing on the shoulders

of previous dystopian lit and not making much of a unique contribution. It reads more like a jungle comic than Pulp

Dystopia. The Kilraven series was a continuation

of War of the Worlds and in the end seemed to be more about a post apocalyptic Marvel

Universe than a real world dystopia.

Greetings, Ajax! I wanted to say hi. I stumbled upon your site a short while back, and I have really enjoyed reading through all of the material. I have also downloaded the published WDMA rules, and discovered to my surprise that I somehow received a "Designer" credit. I'm not sure what I did to earn that, but thanks! I would definitely be in the market for a future printing of the new rules. I can be contacted at {firstname}.{lastname} {at} comcast {dot} net. --- a member of your old west suburban gaming group

ReplyDeleteWow that was odd. I just wrote an very long comment but after

ReplyDeleteI clicked submit my comment didn't show up. Grrrr...

well I'm not writing all that over again. Anyways, just wanted to say excellent blog!